After nearly a decade-long recording hiatus, iconic force of nature Diamanda Galás has resurfaced with pair of themed albums of characteristically dark covers and interpretations.  Linked by two different versions of the traditional "O Death," the partially studio-recorded All The Way revisits the familiar territory of classic blues and country while the St. Thomas the Apostle live performance delves into the even more familiar subject of death.  Both albums have their moments of brilliance, but the St. Thomas performance is arguably more accessible, if only because Galás's demonic operatic flourishes  feel a bit more at home in her own arrangements of poems and texts than they do when all that firepower is directed at, say, a Johnny Paycheck song.  Also, it is quite a bit looser and more varied.  Accessibility is quite relative with an artist as simultaneously beloved and polarizing as Galás though, as even the sultriest, sexiest jazz standards can erupt into primal, window-rattling intensity with absolutely no warning.

After nearly a decade-long recording hiatus, iconic force of nature Diamanda Galás has resurfaced with pair of themed albums of characteristically dark covers and interpretations.  Linked by two different versions of the traditional "O Death," the partially studio-recorded All The Way revisits the familiar territory of classic blues and country while the St. Thomas the Apostle live performance delves into the even more familiar subject of death.  Both albums have their moments of brilliance, but the St. Thomas performance is arguably more accessible, if only because Galás's demonic operatic flourishes  feel a bit more at home in her own arrangements of poems and texts than they do when all that firepower is directed at, say, a Johnny Paycheck song.  Also, it is quite a bit looser and more varied.  Accessibility is quite relative with an artist as simultaneously beloved and polarizing as Galás though, as even the sultriest, sexiest jazz standards can erupt into primal, window-rattling intensity with absolutely no warning.

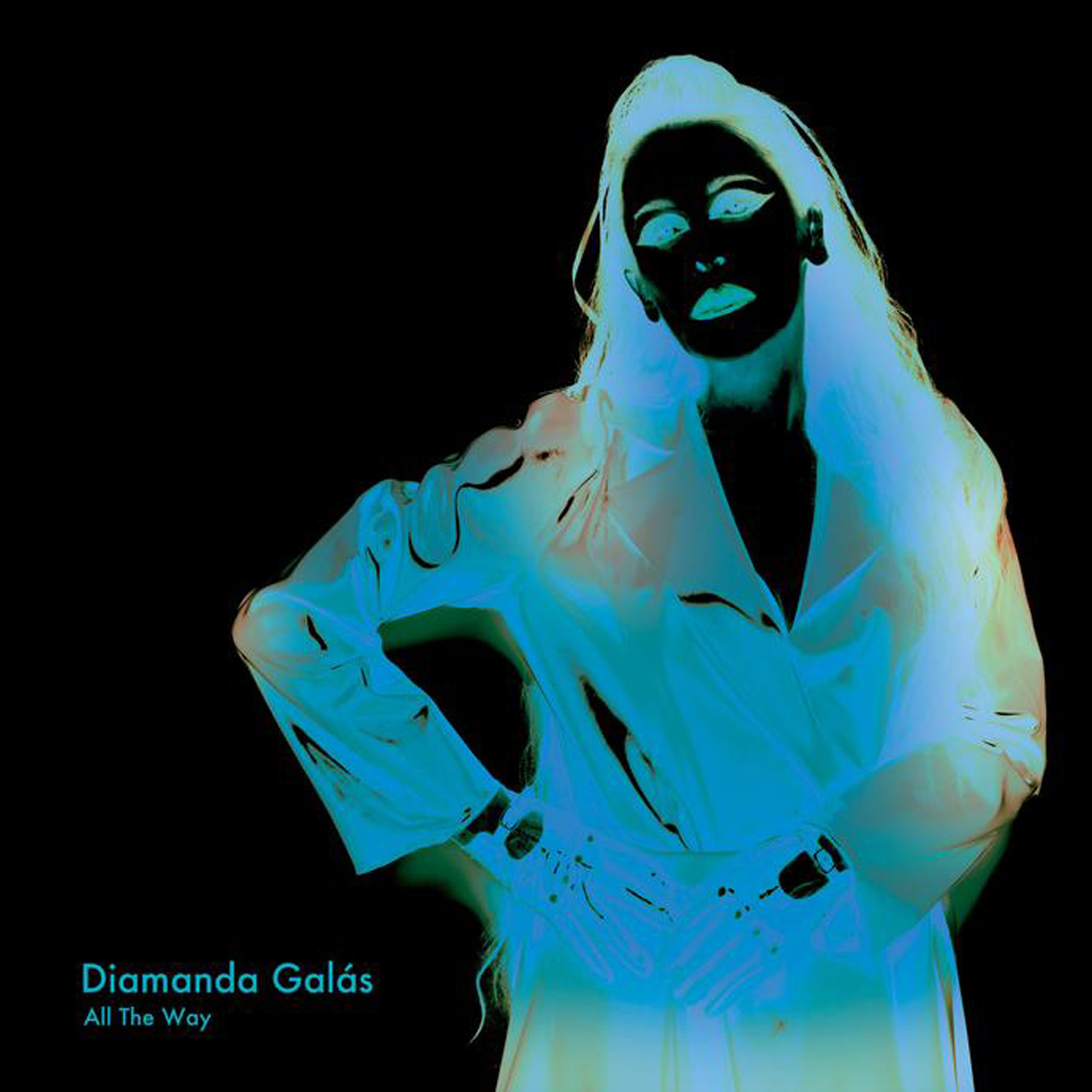

All the Way kicks off with the studio-recorded title piece, a song that I best remember via Frank Sinatra.  All similarities to Sinatra are strictly limited to the lyrics though, as the sometimes dissonant and erratic avant-jazz piano and Diamanda's alternately hissing and snarling vocals makes the song feel like a bitter and threatening warning from a wronged woman who is probably on her way to go repeatedly stab a happy couple.  Curiously, it gradually becomes somewhat less threatening and a bit more conventionally melodic as it progresses, which is almost more disturbing, as it could mean that menace is slowly becoming mingled with better memories or just that the narrator is prone to unpredictably shifting moods.  In either case, it is quite an unsettling piece and a prime example of the sort of disturbing twists on the torch song genre Galás excels at here, as she subverts the expected kittenish seduction into something that feels a lot more like being mesmerized by a succubus...then being ferociously ripped apart.  Much like the rest of the album, "All the Way" is essentially just Galás alone at a piano (raw and undiluted), though it does offer some rare and subtle studio embellishment in the form of well-placed echoing after-images.

The hot streak that began with "All the Way" continues uninterrupted for the entire first side of the album, as the smoldering "You Don’t Know What Love Is" is especially electrifying.  Galás also returns to the Chet Baker chestnut she so harrowingly interpreted on Malediction and Prayer ("The Thrill is Gone"), but plays it fairly straight this time around, taking a tender and mournful tone rather than a feral one…initially, at least–it takes a hard turn towards the cathartic, maniacal, and obsessive near the end.  I suppose that unpredictable trajectory, aside from her prodigious vocal range and power, is what makes Diamanda's interpretations of these standards so unique: I never know when a Pandora's box of howling anguish is about to be unleashed.  The following foray into Thelonious Monk's "Round Midnight," however, is an unexpected aberration to that trend, as Diamanda gives her throat a brief rest to showcase her mercurial piano virtuosity.  "Round Midnight" proves to be the calm before the storm though, as Galás plunges into the album’s bizarre and eccentric centerpiece, "O Death."  It is a piece that she seems singularly fixated upon, as it appears in live form on both of her new releases in addition to its previous appearance on 2008's Guilty Guilty Guilty.  I suspect it is exactly the kind of piece that separates the serious Diamanda fans from the more faint-hearted dabblers like myself, as its simple piano blues erupts something that sounds like an entire musical theater production or one-woman show condensed into a disorienting 10-minute tour de force of howling, shrieking, and ululating.  I truly do not know what to make of it, as the high points are absolutely face-melting, but it makes for a thoroughly unsettling and challenging listening experience as a whole (Galás even seems to be speaking in tongues at one point).  It feels embarrassingly lazy to observe that Diamanda sounds "possessed," but that is exactly how she sounds during the more unhinged and explosive moments of "O Death."

In theory, that demented freeform hurricane should be an impossible act to follow, but the coda of Johnny Paycheck’s "Pardon Me, I’ve Got Someone to Kill" feels weirdly appropriate.  Naturally, it does not sound at all like the original, as Galás inventively transforms it from vaguely "outlaw country" territory into something resembling a rapturous gospel piece.  It also has an almost conversational tone in places, as if she is cheerfully explaining the liberating pleasures of murdering one's former lover  to a roomful of rapt (yet understandably somewhat confused) children.  After the harrowing eruption of "O Death," nothing could be more perversely welcome.

Samples:

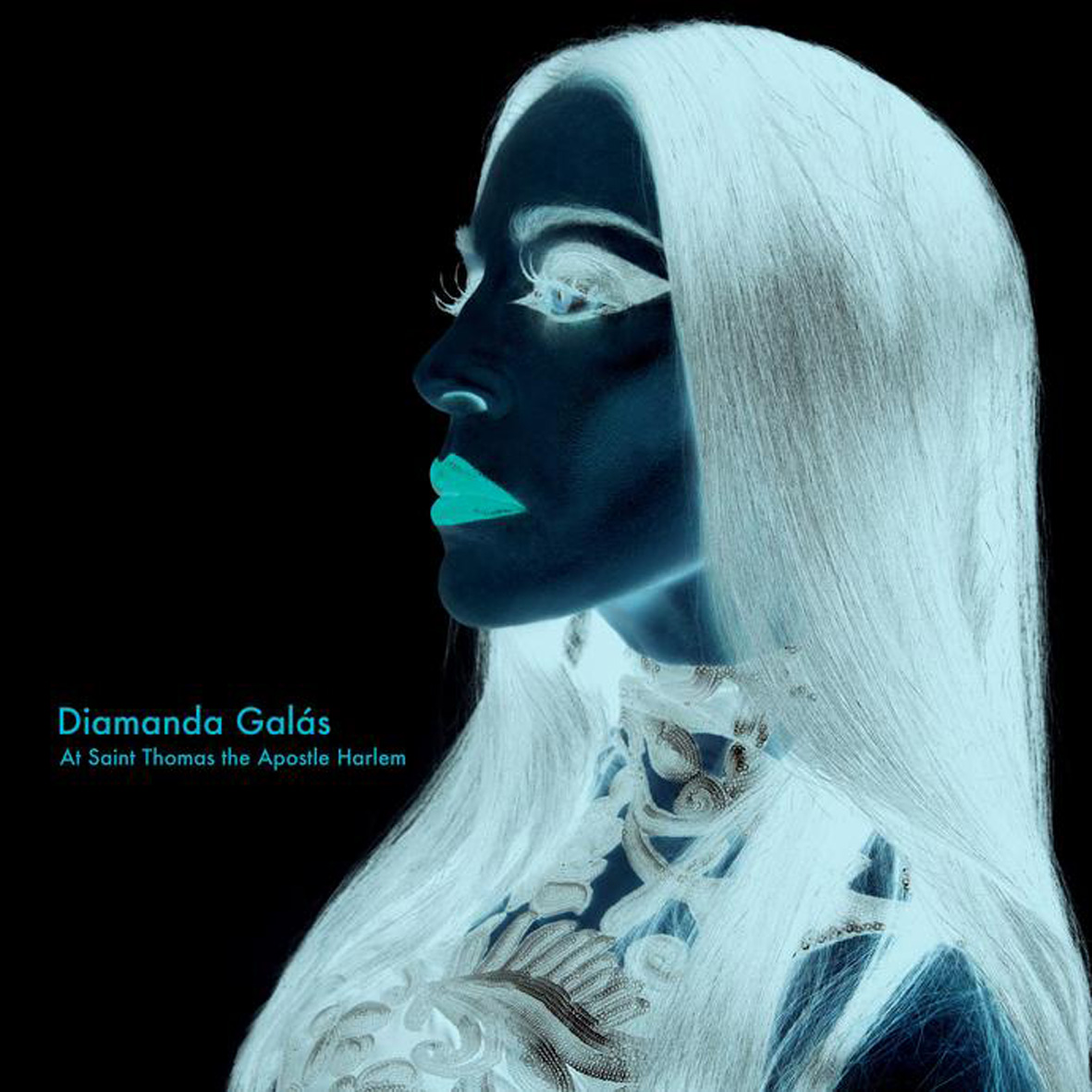

Galás has made no secret of her love of Maria Callas, so it is fitting that her St. Thomas the Apostle performance opens with a dose of relatively pure opera in the form of her own adaptation of a text by Cesare Pavese.Although it roughly translates as "Death Will Come and Will Have Your Eyes," it is not nearly as terrifying as some of Galás's jazz standards, opting instead for a kind of ghostly beauty.  Much like All the Way, the Pavese piece and the seven other songs that follow all feature Galás alone at her piano, which suits the material just fine.  This album feels a bit more loose, improvised, tender, and informal though, as if I am listening in on Diamanda playing late at night in her living room after a couple glasses of wine (rather than listening to her channel an intense parade of murderous seductresses and spurned lovers).  That casual charm extends to the eclectic nature of the selections as well–though death is the unwavering theme, Galás effortlessly shifts languages and moods from song to song.  For example, "Anoixe Petra" sounds like a rousing Greek wake, while her cover of Albert Ayler's "Angels" sounds like a meandering gospel piece that intermittently erupts into atypically joyful upper-register vocal pyrotechnics.  It is nice to hear some major chords every once in a while, as darkness needs contrast to make its full impact.

After Ayler, Galás shifts to German, giving voice to a text by poet/radical Ferdinand Freiligrath, which is an intriguing journey through rumbling low-end piano flourishes, dissonant chords, tender lyricism, lovely ascending melodies, and a crescendo of blood-curdling banshee howls.  French poet Gérard de Nerval turns up to the party as well, as Diamanda transforms his ode to Artemis (the huntress and protector of womankind) into a snarling lament.  Apparently the French language is an especially fertile ground for musings on mortality, as a pair of Jacques Brel pieces make the cut as well ("Fernand" and "Amsterdam").  His chansons are an especially good fit for Galás's aesthetic, as their inherent melodrama and theatricality make her biting and snarling divergences a comparatively short trip up the intensity dial.  Brel's "Amsterdam" is especially delightful and spirited, as Diamanda seems to be channeling a boisterous, fast-talking prostitute and having a wonderful time doing it.  I daresay I would even describe it as "fun," albeit in a "macabre show tune" kind of way.  Less overtly fun is yet another incarnation of "O Death," which is the lengthy centerpiece of this album as well.  I definitely like this version a lot better than the one on All The Way though, as its freewheeling sassiness and cackling bluesiness is considerably less shrill than its sister version.  Of course, Galás still hits her share of unearthly peaks and bestial screeches and howls, but they feel more natural and ecstatic here.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the fact that I was actually at one of the two Harlem shows, I did not have particularly high expectations for At Saint Thomas The Apostle, as I generally find live albums extraneous and indulgent.  More importantly, watching Diamanda perform live is a singularly mesmerizing and profound experience–one that I knew could not possibly be approximated by a mere recording.  This album offers quite an appealing and surprisingly intimate consolation prize though, as Galás feels less like An Important Artist Creating Important Art and more like a charismatic creative supernova unselfconsciously and joyously burning through all of her favorite songs for a church full of devoted fans.  Naturally, Galás's more terrifying, intense, and iconic work will continue to be her legacy, but Saint Thomas the Apostle is probably the best entry point to her singularly uncompromising oeuvre that anyone could ever hope for…aside from, of course, attending one of her actual performances: anyone who can walk away from one of those unmoved is categorically dead inside.

Samples:

Read More