This unusual reissue quietly entered the world last December when everyone was frantically obsessing over the year-end lists and features, so it did not get nearly the attention it deserved. It is certainly an odd release for a couple of reasons, but the most obvious one is that a 35-year-old album of bird songs was resurrected by a record label best known for avant-garde and experimental music. The other is that Birds of Venezuela was just one of over one hundred albums recorded and released by French ornithologist Jean-Claude Roché. That naturally begged the questions "What makes this album the special one?" and "Who exactly is this for?". As it turns out, the liner notes by David Toop answer the former and the album itself decisively answered the latter: this album is for me because it is amazing. In fact, Toop actually started planning a trip to the Amazon soon after hearing this Birds of Venezuela and I probably would have done the same, as a strong case could be made that the most texturally and melodically compelling music scene of the mid-‘70s was the Venezuelan rain forests.

This unusual reissue quietly entered the world last December when everyone was frantically obsessing over the year-end lists and features, so it did not get nearly the attention it deserved. It is certainly an odd release for a couple of reasons, but the most obvious one is that a 35-year-old album of bird songs was resurrected by a record label best known for avant-garde and experimental music. The other is that Birds of Venezuela was just one of over one hundred albums recorded and released by French ornithologist Jean-Claude Roché. That naturally begged the questions "What makes this album the special one?" and "Who exactly is this for?". As it turns out, the liner notes by David Toop answer the former and the album itself decisively answered the latter: this album is for me because it is amazing. In fact, Toop actually started planning a trip to the Amazon soon after hearing this Birds of Venezuela and I probably would have done the same, as a strong case could be made that the most texturally and melodically compelling music scene of the mid-‘70s was the Venezuelan rain forests.

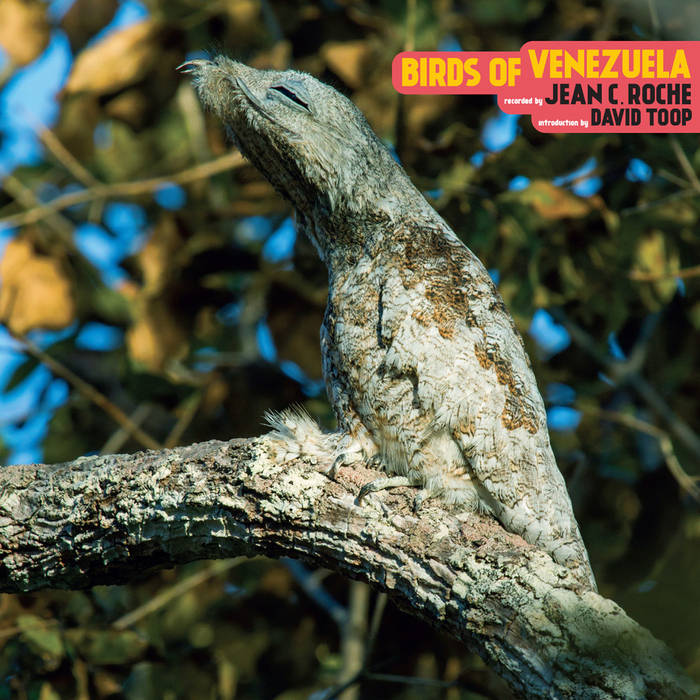

Given that this is an album of field recordings of birds, it is no surprise that the birds themselves are the stars.Among the many participants, the pootoo portrayed on the album’s cover is the biggest draw of all, as the liner notes breathlessly describe it as "a metal-looking bird" that is "one of the sonorous curiosities of this mad nature."Toop himself encountered the pootoo's song on his own Venezuelan trip and described it as "like lost ghost-souls crying out to the living" and one of the "most affecting" listening experiences of his life.With source material like that, Birds of Venezuela certainly would have been a fitfully striking release as just a collection of pure field recordings, but it is actually elevated to a higher plane of art and vision by Roché's unusual collage approach to mixing.Unlike many bird-based albums, Roché’s intention was not to document and isolate the individual songs.Rather, he ambitiously attempted to create a vivid and vibrantly alive "stereo concert" that roughly replicated the experience of being inside the delightful cacophony that erupted every dusk and dawn in Venezuelan forests.Amusingly, Roché unintentionally became an actual avant-garde artist a few years later, as the Lyon-based GMVL started presenting evening events where they would play five of Roché's stereo concerts at once in a park.Depending on one's location in the park, it was possible to experience a blurring together of sounds from various continents at once.Jazz musicians soon began approaching Roché to tell him that they liked his work.I expect most ornithologists do not experience that level of fame in art scenes.

Each of the five pieces assembled here has its own distinct character and subtly surprisingly trajectory.For example, the opening "Ocumare" initially sounds exactly like what I would expect from an album of Venezuelan bird songs, then unexpectedly erupts into a bubbling and hallucinatory crescendo with the help of a chorus of frogs.In "Gran Saba," one especially singular bird call that I recognized from a Dead Can Dance album stands out, but the depth and the warbling, seesawing dynamics of the backdrop are perhaps even more compelling (until it is all enveloped by the sinister roar of howler monkeys, anyway).The shorter "Rancho Grande" revisits that immersive, multilayered sound field of chittering, gibbering, and chirping sans monkeys, acting as a palette-cleanser of sorts before than album's bizarre and memorable second half.As a composition, the lengthy "Palmar" is arguably the album’s zenith, as it undergoes a mesmerizing and surreal transformation that strikingly feels industrial or futuristic at times.Naturally, Roché saves the pootoo's appearance for last, as their haunting call sneakily creeps up through the otherwise happy chirping and gurgling of "Guanare/Barinas."Toop's description of the sound as "ghost-souls" is a fairly apt one, as the pootoo's call does have an eerily human sound, albeit one that sounds smeared and processed.To my ears, it is not necessarily more attention-grabbing than the album's previous frog eruptions, but it is deliciously unnerving in its context.It feels like Roché presents a lively, colorful, and playful swirl of sounds, then stealthily pulls back a curtain to reveal the darker and more disturbing reality that also exists in the Amazonian rain forests.

One element of truly great music that I am always chasing is a masterful feat of illusion that erases any overt traces of deliberate compositional arc, recognizable instrumentation, rigid chord structure, or the hand of the artist.I did not expect to find such a perfect example of that achievement here, as I have heard plenty of bird-song albums before and I have never been particularly dazzled by them.Roché's stereo concerts, however, elevate a chorus of isolated pretty sounds into a trilling, chirping symphony of genuine depth and textural genius.Many years ago, I got to experience a Francisco López piece that was essentially processed rain forest sounds played with maniacal intensity and crushing volume.Unsurprisingly, it was an amazing and overwhelming experience.Birds of Venezuela is every bit as compelling as that, albeit a far more subdued variation: "birds as ambient soundscape" rather than "birds as noise assault."As a pure musical experience, this album is a virtuosic masterclass in dynamics and layering, as there a vibrant mélange of constant movements, shifting distances, loop-like rhythms, and melodic unpredictability pervading all these pieces.I know nothing about bird and frog psychology, so I have no idea how much the individual participants on this album consciously interact with other species sound-wise.They all seem to have a very important role that complements the roles of others though: Birds of Venezuela is like hearing a vast improv ensemble operating on a hive-mind level and it feels both effortless and transcendent.

Samples can be found here.

Read More