Drew Daniel and M.C. Schmidt have abandoned their usual working methods for their new album. Gone are closely mic'd, digitally processed samples of non-musical objects, and along with them the heavily conceptual processes that have often made the liner notes of past Matmos albums as much fun as the music itself. In their place: synthesizers, synthesizers and more synthesizers.

Drew Daniel and M.C. Schmidt have abandoned their usual working methods for their new album. Gone are closely mic'd, digitally processed samples of non-musical objects, and along with them the heavily conceptual processes that have often made the liner notes of past Matmos albums as much fun as the music itself. In their place: synthesizers, synthesizers and more synthesizers.

When Matmos first announced that they would be making an "all synthesizer" album, it seemed like a drastic sea change for a group known for taking full advantage of digital technology to sample, process and sequence bits of audio. Instead of contact mics and laptops, Matmos would be set adrift in the world of analog synths, working without a net, trying to produce music by turns conceptual and whimsical with primitive technologies: voltage controlled oscillators, envelope generators, low frequency oscillators and ring modulators linked together by a maze of patchcords, sequenced and synced using outmoded CV technology, recorded directly to tape with absolutely no subsequent digital processing. Well, it turns out that this was all an elaborate fantasy on my part, a misconception born of my own annoying purist tendencies. In fact, Matmos have not gone "all analog" at all, and Supreme Balloon utilizes a wide array of digital synthesizers, software synths, MAX/MSP patches, MIDI synchronization and computer-based sequencing. The only real overriding concept on the album is "direct music," sound synthesis captured through the wire, rather than through the air. This means no microphones, but everything else in their arsenal is fair game.

I must admit to being disappointed by discovering that the concept wasn't quite as puritan as I had imagined. This certainly isn't Matmos' fault, but their "all synthesizer" album does have the disadvantage of being released at a time when the American and British underground music scene has become obsessed with analog synthesis, DIY home-built modular electronics, circuit bending and primitive recording methods. Many small indie labels have recently popped up with rosters consisting largely of classicist electronic music produced by vintage synthesizers. The music being made by these artists ranges from techno to noise to coldwave/industrial to 1960s Moog novelty throwbacks, but all of it shares in common a distaste for laptops and prefab, mass-marketed Korg synths and Roland grooveboxes, with their too-familiar presets and limited ranges of sound. There can be no doubt that there is something of a conservative streak in this movement; a backlash against the wide availability of pirated software that promises to instantly transform any suburban hipster into the second coming of J. Dilla or Autechre. Conservative though it may be, much of the music is fascinating, and the ascetic stance of its artists lends it a quality that stands out in the digital age. Matmos don't seem to care about any of this, and indeed Supreme Balloon is pretty much a Matmos album with one extra ground rule. As such, the concept feels a bit slight, and if the album itself contains many isolated moments of brilliance, it nevertheless does not share the delightful conceptual complexity that make albums like The Rose Has Teeth in the Mouth of the Beast and A Chance to Cut is a Chance to Cure so memorable, and amenable to analysis.

I am aware that all of the above is simply baggage I am bringing to the album. How does the music sound on its own terms? The answer is manifold. Supreme Balloon pays homage, at times, to the early gurus of electronic music, both in its popular and academic forms. This necessarily involves various reference points such as Wendy Carlos, Delia Derbyshire, Perry and Kingsley, Pierre Schaeffer and the INA-GRM group, Terry Riley, White Noise, Tomita, Klaus Schulze and Cluster. In this sense, the album is just as populated with "personalities" as The Rose Has Teeth. Without recourse to objects or texts, the references are more subtle, but still present. This results in an album that feels at times like a constellation of reference points, especially tracks such as "Les Folies Francaises" and the title track, the former a performance of a French baroque piece using a Switched-On Bach-style patch on a Korg MS2000, and the latter a side-long tribute very much in the kosmische vein, Tangerine Dream by way of Thighpaulsandra. But this is not the whole story: this album is not just a tribute to electronic musicians past. The album also shares with Matmos' previous work a penchant for whimsy and humor, and a predilection for infectious, simple melodies in the midst of crowded compositions that rarely forsake the "groove" for very long. A song like "Exciter Lamp" is a case in point; a weird collection of alien synth patches, jarring tones and oddball sequences that do not fail to coalesce into the crunchy, melodic, bottom-heavy techno for which Matmos have become known.

There are also some great guest players on Supreme Balloon, including the Arkestra's Marshal Allen on "Mister Mouth," playing the EVI, sort of an electronic version of a claviola. Matmos take full advantage of digital technology to chop up Allen's solo and process it into funky, resonant techno. The track is accomplished, but I can't help but feel like something is lost in translation amidst all this processing. And what is lost is any trace of the stochastic. One of the things that makes hand-played (or mouth-played) analog synths interesting is their potential for randomness, unreliability, unpredictable jumps in pitch and odd bits of noise and interference. By smoothing off the rough edges and treating the sounds like just another object to sample and process, I feel as if Matmos missed a chance.

Again, though, these complaints find me going "outside the text" a bit, looking for something that might have been, rather than what is there, which is frequently brilliant. My favorite track on the album proper is the title track, a beautiful, longform synth excursion that unfolds in a leisurely way, gathering together hyperelliptic surfaces and resonant emanations to create areas of tension and resolution, turbulence and placidity. The use of some offbeat musical gadgets—an electronic tabla machine and the Flame MIDI Talking Synth among them—satisfies the gearhead in me, while adding outre textures that Matmos can truly call their own. It's an awesome journey that pays homage to Cluster and Tangerine Dream, without ever being overly reverent. The Latin-inflected "Rainbow Flag" opens the album on a kitschy note, in which easy listening potential is complicated by clusters of high-pitched bleeps. It's not quite the flamboyant gay pride parade suggested by the track's title, but it's close enough, a joyous assemblage of campy musical references, from theremin-heavy sci-fi soundtracks to the unmistakable sounds of the Stylophone, probably the cheapest instrument used by Matmos in the making of the album. "Cloudhopper" ends the album on an ambient note, a spacey circulation of events that sounds perhaps closest to what my original, purist fantasies had imagined for the album.

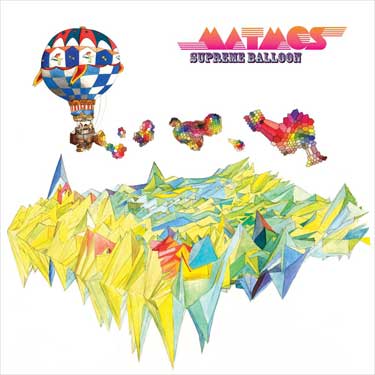

Supreme Balloon is unique in having five bonus tracks amid its various formats; four on the iTunes and double-LP versions, and one on the Japanese CD version. The quality of these tracks is average to amazing. "Staircase," which appeared first on the Peace (for mom) compilation, sounds like an electronic version of Lubomyr Melnyk's minimalistic piano arpeggiations, interesting but slight. The best of the bonus tracks is definitely "Hashish Master," featuring the incomparable Terry Riley on ARP 2600. The dark, druggy tones of the track bring it close in mood to the Coil of Astral Disaster, intense repetitions and decadent, Dionysian undercurrents. In my view, this track should have been included on the album proper, even if it might have broken up the lighter, kitschier vibe of the rest of the album. "Orban" is an admirable tribute to acid techno, containing plenty of eyeball-vibrating MDMA smacks, playing with the stereo channels in an engaging way, even in the absence of any sort of central hook to hold onto. The album artwork deserves a special mention, with its postmodern combination of 1889 World's Fair French Pavilion aesthetics, with a colorful, fractalized landscape seemingly generated by topological algorithms.

Taken together with its bonus tracks, Supreme Balloon is an admirable tangent for Matmos, full of stunning synthscapes and groovy complexity. Though it often seems to be working at cross purposes with itself, staging a sometimes uncomfortable conversation between the asceticism of classic electronic musics and the Matmosian maximalist sample-and-process strategies, there are enough winning moments to more than recommend it. I predict that this album will inspire some accusations of dilletantism to be directed towards the duo, as their dip into the often rarefied realm of direct music delights in its own impiousness, but I suspect that Drew Daniel and M.C. Schmidt won't spend much time worrying about such things.

samples:

Read More