- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In addition to the cassettes reviewed by Creaig Dunton last week, Anthony Mangicapra has also been busy releasing some terrific little CD-Rs on the world. Short and sweet, these two releases further demonstrate why Mangicapra and his associate Ryan Martin (of the group York Factory Complaint and label Robert & Leopold) are making some of the most engaging music this year.

In addition to the cassettes reviewed by Creaig Dunton last week, Anthony Mangicapra has also been busy releasing some terrific little CD-Rs on the world. Short and sweet, these two releases further demonstrate why Mangicapra and his associate Ryan Martin (of the group York Factory Complaint and label Robert & Leopold) are making some of the most engaging music this year.

Robert & Leopold / Goat Eater Arts

Live at the Brooklyn Fashion League consists of single piece, "This Is All Very Familiar," which finds Mangicapra joined in his work as Hoor-paar-Kraat by Martin for about 15 minutes. Beginning with metallic scrapings and odd snippets of vocals, it picks up where earlier Hoor-paar-Kraat works have left off. Slurred animal noises and a throbbing hum fill out the space to create a busy but not too cluttered arrangement (though it does become quite dense towards the end). Despite being an amalgamation of mostly unmusical sounds, the performance has a lyricism that is largely lacking from contemporary noise and experimental music.

samples:

Mangicapra’s studio collaboration with Martin, Golden Hazrat, takes on a far more varied approach compared to Live at the Brooklyn Fashion League. Overall, Golden Hazrat reminds me of a condensed version of Throbbing Gristle’s Journey Through a Body both in range and in tone. Building up from a chthonic rumble, scrapes and echoing noises create a sinister vibe that all of a sudden gives way to a serene sound of water flowing and dripping.

Just when it seems like the fluvial beauty is there to stay, harsh feedback (or are they heavily manipulated vocals?) erupts like a surprise electrical storm before morphing into the sounds of subway trains. The piece continues to shift and swerve around my ears in unpredictable but fascinating ways, the combination of Mangicapra and Martin together is as good, if not better, than their respective solo works.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

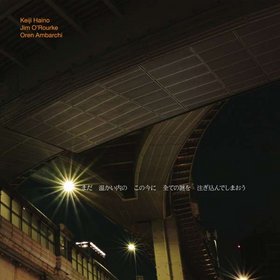

It seems this trio has made a tradition of releasing a new recording every year and it has become a welcome addition to my calendar. This album sees the group in flying form, expanding their remit to include a much wider spectrum of sounds ranging from delicate atmospheres to psychedelic explosions of freak out rock’n’roll. It is an exciting and, dare I say it, fun trip which may be their best offering yet.

It seems this trio has made a tradition of releasing a new recording every year and it has become a welcome addition to my calendar. This album sees the group in flying form, expanding their remit to include a much wider spectrum of sounds ranging from delicate atmospheres to psychedelic explosions of freak out rock’n’roll. It is an exciting and, dare I say it, fun trip which may be their best offering yet.

Black Truffle / Medama Records

On the opening piece, "Once Again I Hear the Beautiful Vertigo Luring Us to "Do Something, Somehow"," the trio become a quintet as they are joined by legendary minimalist composer Charlemagne Palestine and singer-songwriter Eiko Ishibashi (who has collaborated with Keiji Haino and Jim O’Rourke on separate projects before). Everyone is playing wineglasses to create a shimmering canvas for Haino’s vocals to be applied. This is spine-shivering stuff up with Haino’s most ethereal works. When Haino's guitar, Oren Ambarchi’s light percussion and O’Rourke’s cavernous bass kick in towards the end of the piece; it is like a holy prayer has become a solid reality.

The music continues in a down-key, meditative mood with "Who Would Have Thought this Callous History Would Become My Skin." Haino switches to flute which could easily fit in during one of Eric Dolphy’s quieter moments. His vocals are also some of the closest he has come to standard in a long time. Ambarchi and O’Rourke make themselves felt rather than heard, gently filling in the spaces around Haino’s performance. It is on the borders of jazz and the various members of the group’s own styles but never truly settles down in any convenient box.

A more familiar side to the group appears with the storming power of "Only the Winding "Why" Expresses Anything Clearly" where Haino’s buzz saw guitar cuts through the ether. Ambarchi’s drumming becomes emphatic but he remains firmly in control. O’Rourke remains in the shadows, mainly sliding along the bass guitar’s fretboard and adding the occasional riff here and there. It stands out not only on Now While It's Still Warm Let Us Pour in All the Mystery but also in the group’s growing back catalogue. If I was assembling an introductory compilation to Haino and his various groups, this would be one to lure someone in.

Now While It's Still Warm Let Us Pour in All the Mystery continues in a similar manner with the group rarely taking their foot off the pedal for the rest of the performance; though, there is a lovely melodic bit thrown in by surprise at the end of "Even that Still Here and Unwanted Can You and I Love It Just Like Us It Was Born Here Too." However, the final piece sees them change direction one last time which manages to combine the murk of a silty river with the crystal clarity of the stars on a cloudless night. From my perspective, the Haino/O’Rourke/Ambarchi trio continue to surprise and delight me and, judging from their repeated collaborations and development, it seems that it has the same effect on them too.

samples:

- Once Again I Hear the Beautiful Vertigo Luring Us to "Do Something, Somehow"

- Only the Winding "Why" Expresses Anything Clearly

- Now While It's Still Warm Let Us Pour in All the Mystery

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

In 1997, as the last of the tenth generation Thunderbirds rolled off the Ford assembly line in Lorain, Ohio, Jason Molina released his debut album and first EP for Secretly Canadian. The Lorain native had two 7" singles to his name when his self-titled debut arrived in April. Hecla & Griper snuck in before Christmas that year, loaded with terse songs, a bigger bottom end, and a tougher sound for the winter. Secretly Canadian’s 15th Anniversary Edition tacks on four new-ish songs, two of them exciting, previously unreleased Hecla versions of "Heart Newly Arrived" and "One of Those Uncertain Hands," which both first showed up on 1998’s Impala.

In 1997, as the last of the tenth generation Thunderbirds rolled off the Ford assembly line in Lorain, Ohio, Jason Molina released his debut album and first EP for Secretly Canadian. The Lorain native had two 7" singles to his name when his self-titled debut arrived in April. Hecla & Griper snuck in before Christmas that year, loaded with terse songs, a bigger bottom end, and a tougher sound for the winter. Secretly Canadian’s 15th Anniversary Edition tacks on four new-ish songs, two of them exciting, previously unreleased Hecla versions of "Heart Newly Arrived" and "One of Those Uncertain Hands," which both first showed up on 1998’s Impala.

There’s nothing in Songs: Ohia’s first recordings that point to where Molina would end up on albums like Ghost Tropic or Didn't It Rain. Early on, he had somewhere to be and he wanted to get there fast. No nine minute serenades with bluesy flourishes, no long instrumental passages with droning organs and bird calls —just a small band, some peculiar verses, and maybe a chorus or two where the lines bear repeating. "Pass," Hecla’s opening song, lasts just one minute. Jason sings for about half that time. It’s more like a punk song than anything in the Americana/Palace-worship catalog, and it's catchy as hell. "East Last Heart," the longest song on the EP at four minutes, ends precisely when it needs to, and with very little ornamentation: some dramatic piano chords to complement the bottom-heavy crawl of the tenor guitar and bass, and Jason singing "rich kid I’m talking to you." That’s it. Cut, next song.

Even the slow tunes are fleet of foot. "Reply & Claim," a re-purposed version of "Citadel (Tenskwatawa)," is just a hair longer than the original, but passes with more momentum thanks to the extra instrumentation. The instrumentation is only bass and drums, but it sounds more like a rock song now and Jason’s delivery is a touch more urgent too, to keep the energy in proportion with the duration. Plus there aren't any saxophones or clarinets brightening things up, so there’s no airy relief from Molina’s frequently dark lyricism and insistent delivery. The closest Hecla & Griper gets to relief is a cover of Conway Twitty’s "Hello Darlin'," which is almost funny, but still badass. Jason talks through some of the lyrics, sounding proud and resigned simultaneously, and half-amused that he’s recording a Conway Twitty song.

The bonus songs are an odd bunch. "Pilot & Friend" is a slightly different version of "The Arrogant Truth" from the Our Golden Ratio EP (1998), and "Debts" is actually "To the Neighbors of Our Age," which first saw the light of day on Songs for the Geographically Challenged Volume 2, released by Temporary Residence in 1997. "Debts" points the way to Impala with its quiet organ melody, but still fits the Hecla bill just fine. I assume "Pilot & Friend" was recorded around the same time, but without liner notes all I can do is assume. It isn't out of place, but why put a song from another EP on here?

But I'm being grumpy about a great song from an EP I don't have anyway. For fans already acquainted with everything Jason did, the new versions of "Heart Newly Arrived" and "One of Those Uncertain Hands" are worth getting excited about. They feature the Hecla & Griper instrumentation and are more cleanly recorded, without echo or reverb. Instead of being moody and atmospheric, they’re lean and propulsive—mean sounding songs with a touch of heavy metal in them. The Thunderbird may have left Lorain in ’97, but Molina was still representing, dishing out some thunder of his own.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Important Records has issued many great albums over the years, but it just occurred to me today that they have quietly become one of the best-curated reissue labels around.  Case in point: this visionary 1974 suite of hermetic, hallucinatory solo guitar compositions.  Originally self-released, Samtvogel was later reissued twice by the legendary Krautrock label Brain, which is something of a deceptive pairing. Although he worked as Klaus Schulze's roadie and assistant and had an active presence in Germany's free-jazz and space music scenes in his own right, this surprisingly dark and obsessive early effort bears little resemblance to anything else in the Krautrock canon, aside from perhaps Manuel Göttsching's landmark Inventions for Electric Guitar (which was not released until the following year).

Important Records has issued many great albums over the years, but it just occurred to me today that they have quietly become one of the best-curated reissue labels around.  Case in point: this visionary 1974 suite of hermetic, hallucinatory solo guitar compositions.  Originally self-released, Samtvogel was later reissued twice by the legendary Krautrock label Brain, which is something of a deceptive pairing. Although he worked as Klaus Schulze's roadie and assistant and had an active presence in Germany's free-jazz and space music scenes in his own right, this surprisingly dark and obsessive early effort bears little resemblance to anything else in the Krautrock canon, aside from perhaps Manuel Göttsching's landmark Inventions for Electric Guitar (which was not released until the following year).

Notably, Samtvogel ("silk bird") was Schickert's first album, which is both remarkable and weirdly appropriate.  The "appropriate" bit stems from the fact that it is clearly the work of someone who just discovered how cool echo sounds on a guitar and set about abstractly experimenting with it with no real aspirations for anything more.  The "remarkable" aspectq, however, lies in both the single-mindedness with which Schickert pursued his experiments and the self-assuredness of his bold divergence from the exciting, fertile scene around him.  Günter clearly had a unique, fully formed vision from the very beginning and set about realizing it by whatever means were at his disposal, which were quite modest.

Due to the limited, primitive equipment Schickert had on-hand, the recording of these three pieces actually took three months, as all of the heavy lifting was accomplished with just a guitar, an amp, his voice, and two tape recorders.  Given the density and complexity of some passages, that is difficult to imagine, but that is precisely why the recording took so long: Günter had to painstakingly assemble the various layers by recording himself playing along each previous tape, starting over again from scratch every time he made a mistake.  As frustrating as that process must have been, the naked, lo-fi quality of these recordings actually works in Samtvogel's favor, as Schickert's brand of psychedelia feels genuinely, uncomfortably warped rather than like anything resembling mere studio artifice.

Despite that limited palette, each of Samtvogel's three pieces is quite distinctive.  The shortest, "Apricot," opens the album on a fragile, woozy, languorous and uncharacteristically song-like note.  The piece is also quite a cryptic one, as the few words that I am able to make out seem to be about apricot brandy, a topic which sits uncomfortably with the lonely, echo-heavy nightmare the piece gradually becomes.  After that, Günter is very much done with attempting anything that resembles a song in the conventional sense, but he is more than happy to continue being disturbing and nightmarish.  As a result, the following two pieces are much longer and more abstract.  However, while they share a lot of similarities with one another in structure and trajectory, they ultimately wind up in very different places mood-wise.

"Kriegmaschinen, Fahrt Zur Hölle" (or "War Machines, Go to Hell") is the album's darkest, most unhinged piece and consequently its artistic zenith, as Schickert unleashes nearly 20 minutes of dense, dissonantly churningReich-esque minimalist patterns and panning vocal chants buffeted by queasily out-of-tune-sounding jangling.  After the appropriately explosive crescendo subsides, Günter launches into the closing "Walde" ("Forest") with a similarly roiling, massive assault of repeating patterns before unexpectedly giving way to a passage of swooning, melancholy beauty.  For better or worse, that oasis is an ephemeral one, as Schickert keeps a simmering tension rumbling in the background at all times.  Part of me wishes that Günter had allowed his more  warm and dreamlike passages to unfold in a less precarious, threatened manner, but I cannot deny that the piece's unstable and unpredictable nature makes for much better and more striking art than the more conventional piece my battered ears were hoping for.

While Samtvogel is undeniably a very unique, challenging, and forward-thinking recording from start to finish, its single most remarkable characteristic might be that it was not simultaneously Schickert's first and last album.  The mood of these pieces is so claustrophobic and paranoid that it is difficult to believe this was not an aural suicide note, evidence of terminal drug psychosis, or the last communique before Günter completely lost his mind.  Instead, Schickert somehow went on to record a similarly wonderful (if a bit more conventional) follow-up five years later in Überfällig, then later formed the revered (yet obscure) trio GAM.

As much as I loathe the woefully over-used term "lost classic," that is exactly what this album is, as it certainly meets my most exacting criteria: it sounded singularly challenging, audacious, and against-the-tide in 1974 and it basically still sounds completely unique.  Schickert wisely avoided any of the trends or clichés of the day (aside from hating war machines, obviously), so there is virtually nothing on Samtvogel that sounds particularly dated, ill-advised, or derivative.  Granted, there has been no shortage at all of echo-heavy psychedelic guitar voyages in Samtvogel's wake, but I suspect none of them have ever been quite as disconcertingly intimate and haunted-sounding as this one.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Survival is the latest project from Hunter Hunt-Hendrix, along with long time collaborators Greg Smith and Jeff Bobula. It's an aggressive, boastful debut record that blends hard rock and metal tropes and elements of folk. Shedding the blast beat acrobatics that made Liturgy's black metal such a prominent force has done nothing to deter Hendrix's songwriting capabilities, or make the music he plays any less exhilarating. In fact, Survival argues to name Hendrix and crew as some of the most talented metal polyglots around today.

Survival is the latest project from Hunter Hunt-Hendrix, along with long time collaborators Greg Smith and Jeff Bobula. It's an aggressive, boastful debut record that blends hard rock and metal tropes and elements of folk. Shedding the blast beat acrobatics that made Liturgy's black metal such a prominent force has done nothing to deter Hendrix's songwriting capabilities, or make the music he plays any less exhilarating. In fact, Survival argues to name Hendrix and crew as some of the most talented metal polyglots around today.

Survival's a record not about strenuous paces and technical prowess like Liturgy was—relatively speaking, anyway, since it is bound to draw those comparisons. It is an angry, complex metal record full of fast changes and meticulously organized syncopation. But it's a terrestrial one, almost mellifluous at times. First song "Tragedy Of The Mind" captures perfectly the way the record plays out, a pleading insistent barrage of minor key guitar motifs interrupted with sadder, droning vocal harmonies and just enough prog elements to maintain uncertainty.

In Survival's darker moments, like the melancholy chorus of "Original Pain" or the somber folk spirituality of the incredible "Since Sun Revised," there is a genuine loss being felt, and likewise a true joy in "Triumph Of The Good," its powerful crescendos suggesting the success of corporeal virtues like the Olympian art might correlate to.

The album plays only in fully bright moments and utterly dark ones with no half measures. Even on its three song pseudo-suite, the "Freedom" songs, this is either a biblical or a blockbuster kind of freedom, with songs rolling along at breakneck speeds in focused polyrhythms, asking for no less than total compassion for Survival's goals. What they are aren't exactly clear, but they're very convincing.

Hendrix is in the midst of recording another album as Liturgy—whatever the current incarnation might be—and both Smith and Bobula have their hands in a number of side projects, so it's completely possible this might be a one-off recording from the group. Even so, as it stands this is a strong homage to great hard rock and metal, and it's a testimony to the power of never second-guessing your strengths.

samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

This, Zoviet France's first major release in over a decade, originally surfaced last fall as a characteristically cryptic and incredibly limited box set containing rubbings of neolithic Northumbrian stone and a vial of hawthorn berries.  Unfortunately, it completely sold-out world-wide on the day it was released, so most of us never got to hear it.  Until now, anyway, as alt.vinyl has now issued a second (and more affordable) version.  Hawthorn berry enthusiasts will no doubt be a bit dismayed by the hyper-minimal new format (three black vinyl records in three entirely black sleeves), but it certainly fits the music, as 7.10.12 offers up roughly an hour of minimal/quasi-ambient loopscapes.  While they certainly offer many subtle nods to ZF's weirder, more abrasive past, these records feel more like the beginning of a curious new phase than a triumphant return to form.

This, Zoviet France's first major release in over a decade, originally surfaced last fall as a characteristically cryptic and incredibly limited box set containing rubbings of neolithic Northumbrian stone and a vial of hawthorn berries.  Unfortunately, it completely sold-out world-wide on the day it was released, so most of us never got to hear it.  Until now, anyway, as alt.vinyl has now issued a second (and more affordable) version.  Hawthorn berry enthusiasts will no doubt be a bit dismayed by the hyper-minimal new format (three black vinyl records in three entirely black sleeves), but it certainly fits the music, as 7.10.12 offers up roughly an hour of minimal/quasi-ambient loopscapes.  While they certainly offer many subtle nods to ZF's weirder, more abrasive past, these records feel more like the beginning of a curious new phase than a triumphant return to form.

This is a very difficult album to assess with any semblance of objectivity, as a new Zoviet France release is unavoidably colored by both my own expectations and the band's shadowy, fractured history.  Given the group's original shifting, collective nature, the very idea of a "Zoviet France" in 2013 is a bit blurry and perplexing, as only Ben Ponton remains from the early days and most of the key personnel from ZF's prime splintered off to form the very different Reformed Faction.  Consequently, this duo of Ponton and Mark Warren bears only fleeting resemblance to the group responsible for Shouting at the Ground.  Instead, this is a continuation of the ZF responsible for albums like Digilogue and The Decriminalization of Country Music.  That distinction is an important one: 7.10.12 is not a suite of post-industrial/sci-fi tribal experiments–it is more like a monolith of somewhat austere sound art.  That is not inherently a bad thing, but it is certainly a radical stylistic difference.

In its own way, however, 7.10.12 is still a very bizarre and inscrutable effort.  For one, it has a rather unique format that is thematically intertwined with its title and release date: a 7", a 10", and 12" LP.  Secondly, the music has the feel of an evolving narrative or soundtrack, but no clues are given as to what it might mean nor how it might relate to the prehistoric relics/symbols included in the original box.  The song titles, while sometimes evocative, offer little insight at all (and actually are not even provided on the physical release).  Finally, all of these 18 pieces feel like discrete fragments intertwined with one or two simple recurring motifs.  There are many very promising ideas scattered across the three records, but none of them ever seem to evolve into anything more.  Perhaps that is by design, but it is certainly a puzzling structure: intriguing loops constantly appear only to be eventually subsumed by subtle variations of the eternally repeating central drone/ambient motif.  On one hand, that ebb and flow provides an illusion (or reality) of cohesion or larger purpose, but I cannot help but wish that either the primary theme(s) were stronger or that the lesser themes were allowed to grow into something more.

Still, some of the loops show flashes of inspiration, which is both promising and frustrating.  For example, the B-side of the 7" ("The Leaves of the Birch") sounds like a blurred and queasily dissonant music box adrift in a sea of tape hiss, which could have been the foundation for something wonderful.  Instead, however, it just fades in and then gradually fades away after 3 minutes or so.  The other two records are even more riddled with seeming missed opportunities and/or teasing snatches of greatness: imaginary field recordings from hallucinatory forests, warped tribal woodwinds, woozily dreamlike/annoying locked grooves ("Freezeling"), roiling feedback ("Stimatze"), creepily backwards and damaged-sounding swells, and ominous atmospheres abound.  Time and time again, however, Ben and Mark just allow their best ideas to appear and disappear without any apparent evolution.  Again, that may be by design (a series of strange, dreamlike loops taking shape, then dissipating), but it still drives me a little crazy.

Despite my best efforts to unravel the mystery of 7.10.12' or find something profound or fully realized to grasp onto, I cannot help but feel somewhat disappointed by this effort.  I would probably be a lot more charitable if this were not a Zoviet France album, but I love Zoviet France–if that name is going to be resurrected, I want it to be attached to something unambiguously wonderful and distinctive.  Ponton and Warren certainly had many fine ideas, but their impact is is dissipated by a seeming lack (or misuse) of compositional ambition coupled with way too much conceptual ambition.  In a very broad sense, there is a definite logic and cohesion to these three records, as each functions as a self-contained whole while maintaining a strong link to the others.  However, it did not offer much reward for me in an immediate, song-by-song sense: 7.10.12 is essentially a single decent ambient piece chopped up and stretched across three records, interspersed with sketch-like, fleeting glimpses of something a bit more strange and compelling.

I guess I do not fully understand what Warren and Ponton were hoping to accomplish with this effort, nor do I know whether or not they succeeded.  The structure and presentation just seem less-than-ideal for the material, particularly in the 7" format, as having to flip a record after just over 3 minutes makes sustaining an immersive reverie impossible. Still, it is very easy to imagine many of these pieces working beautifully as part of an installation or a soundtrack, even if they a bit too static and fragmented to make any kind of strong statement on their own.  Which, of course, is an unfortunate irony, given that the lack of any kind of text or visual accompaniment basically implies that the records themselves are the entirety of the statement.  Ultimately, 7.10.12 is a bit of an ambitious, promising misfire: I am happy that Zoviet France are back and that they still have something to say, but they have not quite worked out the best way to say it.

Samples:

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

I definitely have a soft spot for industrial music that is so goddamn industrial that it is literally just the sound of machines, so I am the target demographic for this suite of compositions built upon recordings from two French printing facilities.  It is very hard to say how much conventional "composition" was involved though, as Offset often feels like pure audio vérité that has just been cleaned up and EQed for maximum impact.  That is fine by me: regardless of how much or how little studio tweaking, manipulation, and multi-tracking actually took place, Meursault's inspired selection and sequencing yields a very coherent, weirdly hypnotic, and intermittently dazzling whole.

I definitely have a soft spot for industrial music that is so goddamn industrial that it is literally just the sound of machines, so I am the target demographic for this suite of compositions built upon recordings from two French printing facilities.  It is very hard to say how much conventional "composition" was involved though, as Offset often feels like pure audio vérité that has just been cleaned up and EQed for maximum impact.  That is fine by me: regardless of how much or how little studio tweaking, manipulation, and multi-tracking actually took place, Meursault's inspired selection and sequencing yields a very coherent, weirdly hypnotic, and intermittently dazzling whole.

Doubtful Sounds/Universinternational

Offset may seem like an album that draws from very narrow source material, but Pali Meursault's previous album (2011's Without the Wolves) featured a 20-minute piece built from recordings of a melting glacier, which must make recordings of printing presses seem positively liberating and limitless by comparison.  In fact, Meursault actually found these field recordings to be fertile enough material to sustain two fairly different creative directions, one of which is covered on each side of the record.

The first side is devoted to rhythmic patterns or cycles, which is the most obvious theme to explore when faced with a room full of vibrantly whooshing, buzzing, clattering, and clunking machines.  The recordings are predictably and appealingly relentless and mechanized-sounding, but Meursault occasionally surprises me with a striking passage that transcends my limited field recording/collage expectations.  For example, "Cycle 1" sometimes sounds like the labored inhalation and exhalation of some kind of massive metallic monster, while "Cycle 2" sounds absolutely nightmarish when a grindingly dissonant buzz cuts through the crunching and echoing clanks.  Parts of "Cycle 4" even manage to sound like some kind of cutting-edge experimental dance music, as its locked-groove-sounding rhythm starts to resemble a minimalist bass line with dynamically satisfying stops-and-starts.

The second side of album is dedicated to the idea of "flux" and focuses upon the gradual morphing of the machine rhythms, which turns out to be where Meusault's skill and vision truly manifest themselves.  The first of the two lengthy pieces, "Flux 1," is the album's clear highlight, but its brilliance does not become fully evident until the very end.  Instead, it just sounds like constantly clicking, whooshing juggernaut of thrum, which is still quite impressive.  In fact, its sheer relentlessness is utterly mesmerizing, as are its constant minor shifts in texture and density.  Its sole flaw is that the momentum occasionally flags, but that setback is easily eclipsed by the surprise ending where everything coheres into a full minute of shuddering, sinister-sounding machine drone.  The longer "Flux 2" does not quite achieve a similar feat of last-minute alchemy, but is otherwise equally hypnotically propulsive.

Naturally, a vinyl-only album of printing press-based electroacoustic compositions is about as "niche" as it gets, but Meursault unquestionably excelled at what he set out to accomplish: there are definitely some people out there who will want to hear this and they will be very happy when they do.  A small part of me secretly wishes Pali had been more aggressive in his treatment of the material or perhaps collaborated with someone who might have taken the recordings in a more conventionally musical  direction (Offset seems like it would be prime grist for a killer Esplendor Geométrico album), but most of me just appreciates Meursault's commitment to purity and is largely awestruck by what he was able to accomplish with such a willfully limited palette.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

It is not surprising that Tom Smith and Rat Bastard's TLASILA project would release such a baffling work as this. Three discs, four-plus hours (more if the bonus downloadable material is included) and more than 60 artists reworking their material. However, Smith took it upon himself to mix the contributions into long form DJ sets, making it an odd and difficult release to listen to at times. However, with the slew of diverse artists represented, both well known and not so well known, the challenge and effort is worth the listen.

It is not surprising that Tom Smith and Rat Bastard's TLASILA project would release such a baffling work as this. Three discs, four-plus hours (more if the bonus downloadable material is included) and more than 60 artists reworking their material. However, Smith took it upon himself to mix the contributions into long form DJ sets, making it an odd and difficult release to listen to at times. However, with the slew of diverse artists represented, both well known and not so well known, the challenge and effort is worth the listen.

The concept behind this release is this massive collection of artists took improvisational recordings from the Noon and Eternity album, as well as isolated tracks from The Cortège and Épuration albums in order to construct their contributions/remixes, which were then sequenced and blended together to create these distinct, disc-long megamixes that are unrelenting in their approach and duration.

Perhaps it is just my own attempt to make sense of this work, but the three mixes seem to have some sort of genre-associated cohesion to them, albeit in the loosest sense.Disc one, My Finger Was Hooked, seems a bit heavier on the harsh noise end of the spectrum.Opening first with RM74's brittle digital noise of "Bones, Beers and Muscles" and immediately followed up with Howard Stelzer's untitled work of fuzzy tape collages, it takes on a noise vibe right away.With the likes of Carlos Giffoni, Aaron Dilloway and 16 Bitch Pileup appearing, it is some heavy players in the world of noise, even if the mixing makes it occasionally hard to tell who is contributing what.For example, I think Dilloway's contribution of "In Memory of Phil Anselmo" is the one full of cut up Thin Lizzy samples with TLASILA material, but I could be completely wrong.Plus, there are some more music moments around, such as the techno stomp and helium voices of Otto Von Schirach's "Cream Pie 2" keeping things weird.

I Offer Syrup embraces more of the conventional world of electronic music as a whole, from Sickboy Milkplus' "TLASILA THAF Remix" sputtering out with canned drum machine rhythms and stuttering breakbeats to Richard Devine’s microsound laden "V2 Mix".To keep things from being overly similar though, both Dave Philips and Rudolf Eb.er appear in this mix to represent the Schimpfluch scene, as does Thee Majesty, who supplies an abstract ritualistic electronic collage.

Finally, I Offal and I Stumble puts a bit more emphasis on the drone artists, with the likes of William Fowler Collins, C. Spencer Yeh and Kevin Drumm all making their appearances within this disc.Of course it does not stick to some consistent plan, with the likes the random junk cut-ups of Evil Moisture and the harsh noise of Torturing Nurse also rearing their distinct heads.Most surprising, however, is a collage/spoken word appearance by Jared Louche, formerly Hendrickson, of Chemlab (one of my long standing musical guilty pleasures from high school).It is not exceptional really, but his appearance alone made me smile.

While I understand this work from a conceptual standpoint, I would have preferred to have seen these contributions indexed individually, as there are a few pieces I would rather listen to multiple times, and others that, while not especially bad by any means, feel more like filler when placed alongside the more unique artists.It is easy to appreciate and enjoy it as is, but I personally would prefer it as a more traditional compilation album rather than the DJ mix setup that it is.But, given the artist responsible for the project, that sort of rewarding frustration is not surprising in the least.

samples:

- Howard Stelzer - "Untitled (edit)"

- Sickboy Milkplus - "TLASILA THAF Remix"

- Evil Moisture - "BBQ Flavour"

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Menche was the first American noise artist that I was able to embrace, as his approach to art was not only unique (the first work I heard was him processing the sound of salt rubbed between contact mics), but it also was cliché and pretense free. It was simply the work of a man who loved experimenting with different sounds and ways of generating them. While he has stepped back from his more prolific past, the works that he has been releasing are more fully fleshed out and rich, and these two albums are no exception. With Vilké building upon drums, guitar, and wolf howls, and Marriage of Metals focusing exclusively gamelan, the two are vastly different in approach, but the same in quality and structure.

Menche was the first American noise artist that I was able to embrace, as his approach to art was not only unique (the first work I heard was him processing the sound of salt rubbed between contact mics), but it also was cliché and pretense free. It was simply the work of a man who loved experimenting with different sounds and ways of generating them. While he has stepped back from his more prolific past, the works that he has been releasing are more fully fleshed out and rich, and these two albums are no exception. With Vilké building upon drums, guitar, and wolf howls, and Marriage of Metals focusing exclusively gamelan, the two are vastly different in approach, but the same in quality and structure.

The four track, double LP of Vilké is perhaps the most traditionally musical work I have heard Menche having his hand in.The A sides of both records emphasize his more recent fascination with percussion and drums as a starting point for noise collage.Part one is an instantaneous percussive oblivion, with non-stop pounding clattering from left to right throughout.Processed howls of wolves rise up early on, mutated resemble a choir of human voices.Midway through some of his harsher noise tendencies shine through, but even with them in place, there is an overall sense of structure and organization to be heard.

The third part focuses on percussion that is somewhat ritualistic in nature, but cut up and shaped into an unnatural, thudding sound and static laden brittle rhythms.An almost synth-like pattern also opens the piece that soon falls apart into noise chaos, but is then pulled back together again by an expansive, but obscured ambient melody.

The fourth part is perhaps the most different from what I am used to with Menche's work, with erratic, reverb heavy guitar opening and staying prominent throughout the piece, giving a certain metal edge overall.Menche has never made his love of heavy metal a secret, but this is the first time I have heard it overtly shine through in his art.Even when heavy effects and layering leads to a more traditionally noise oriented sound, there is still a bit of metal bleakness to be heard.

samples:

Marriage of Metals is a bit more understated in comparison, however.His processing of gamelan into a deep, low-end thump and overdriven guitar-like noise layers makes it not even vaguely resemble its underlying source at first.A slowly evolving rhythmic structure stands out, and again it has more of an overall musical quality to it, while still resembling nothing traditional on its surface.

On the flip side, the initial sound is not as removed from traditional gamelan, although filtered into a dense, glassy sound as opposed to its traditional resonating clang.It has a delicate timber overall, somewhere between Indonesian music and church bells with a bass heavy undulation beneath.Compared to much of his previous discography, it is downright subtle and beautiful.

While he has gone through periods where new material appeared monthly, Daniel Menche has seemingly taken his time in putting these two works together, and it shows.Distinctly different from one another both in concept and in overall sound, both bear signs of careful artistry and composition, something many artists filed as noise are often apt to not use.The final pieces on both releases also show a developing sense of true musicianship, albeit skewed and idiosyncratic, but employing a sense of structure that rivals that of the best composers.Both stand out as brilliant releases in a long and extremely impressive discography from one of the true unsung masters of sound art.

samples:

- Marriage of Metals Part One (Excerpt 1)

- Marriage of Metals Part One (Excerpt 2)

- Marriage of Metals Part Two

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

While it often feels like the sun has probably set on the golden age of noise, no one seems to have told Lee Howard, as this effort sounds like the culminating masterpiece of a man who has been single-mindedly hellbent on perfecting power electronics for years.  It was time well-spent, as the album's better pieces remind me exactly why I became excited about noise in the first place, as there are few things quite as bracing as a masterfully crafted blast of gnarled brutality.  Thankfully, however, Howard does not rely solely upon force alone, wisely balancing his remarkably articulate ferocity with subtle musicality, clarity, and a highly developed understanding of space, traits which elevate this album far above just about every other recent noise release that I have encountered.

While it often feels like the sun has probably set on the golden age of noise, no one seems to have told Lee Howard, as this effort sounds like the culminating masterpiece of a man who has been single-mindedly hellbent on perfecting power electronics for years.  It was time well-spent, as the album's better pieces remind me exactly why I became excited about noise in the first place, as there are few things quite as bracing as a masterfully crafted blast of gnarled brutality.  Thankfully, however, Howard does not rely solely upon force alone, wisely balancing his remarkably articulate ferocity with subtle musicality, clarity, and a highly developed understanding of space, traits which elevate this album far above just about every other recent noise release that I have encountered.

Before I heard this album, I suspect it would have been extremely difficult to convince me that one of 2013's best albums would be by a British PE guy with an unhealthy Princess Diana fixation, but Who Will Help Me Wash My Right Hand? makes quite an unambiguous case for itself.  Of course, Lee Howard is no ordinary purveyor of power electronics, as he makes immediately clear with the opening "For You I Will," which is built upon little more than an undistorted bass riff, an oscillating hum, a high-hat, and Lee's treated vocals.  Aside from the distorted vocals, the piece bears almost no resemblance to any PE that I have heard, as it is remarkably minimal and boasts a likable "rock" groove, which is probably the most un-PE thing imaginable.

Somehow it all works though, which I attribute almost entirely to Howard's unusual vocals: rather than howling about rape or serial killers, Lee sounds like a man trying to deliver a fitful monologue through a broken microphone that hopelessly clips everything he tries to say.  Buried much deeper in the mix, however, Howard's vocals seem to continue in radically different form, resembling heavily reverbed inhuman howls.  Thanks to the elegant simplicity of the stripped-down music, the strange after-images and echoes of Lee's voice are allowed to be heard and appreciated with complete clarity.  It is an impressive feat that Howard replicates once again with the following "This Dog Has No Master" with slightly different components: conveying simmering menace by moving slowly and leaving a lot of space for his ruined-sounding nuances to make their full impact.

Lee is not always quite that restrained, though, which gives the album some much-appreciated dynamic variation.  The best example of Howard's more ferocious, unhinged side is "Be Forever Green," which begins with a seemingly regressive and shout-y static-fest before it beautifully coheres into a relentless march of massive buzzes of gnarled dissonance that sounds like an unstoppable army of robots slaughtering their way though a post-apocalyptic waste-scape.  On any other album, such a piece would have unquestionably been the highlight, but Howard immediately eclipses it with the epic (and brilliant) "Saltpulse," which more or less tore my head off.

Like "Be Forever Green," "Saltpulse" begins in relatively unpromising fashion, opening with a low drone, a persistent buzzing, and obsessively repeating wobbly swells of mutant bass.  After several minutes, however, it starts to resemble Sonic Youth trying to tune up inside a working trash compactor–still not entirely promising, perhaps, but certainly unexpected. Eventually it starts to sound like everything is shorting out and the song is ending, but then a beautifully melancholy hum slowly fades in from beneath the stuttering wreckage and gradually takes control of the song.  Lee eventually takes the microphone to shout a bit, but the underlying melody transforms his howls and the surrounding crackling entropy into some kind of haunting, ravaged, and rotted elegy that stands as one of the best pieces that I have heard in a very long time.

Naturally, the closing title piece cannot help but be a disappointment after such a tour de force, but its strange 5-minute flurry of lurching swells, bleeps, and oscillating chaos is objectively not bad.  It may not be nearly as compelling and memorable as the preceding four songs, but it does not ruin the spell either, which is the most important thing: any hint of tired PE cliché would have dragged down an otherwise flawless effort.  Rarely have I heard such a perfect mixture of exacting focus, restraint, concision, and intelligence mingled with such crushing heaviness.  This is a truly great album.

Read More

- Administrator

- Albums and Singles

Having had a few years elapse since hearing my last Masami Akita record, this seemed like a good time to step back in. The best thing about following this schedule with his work is that the variation and evolution he has shown in his overall sound keep things consistently fresh. Takahe Collage covers both his harsh noise past and his flirtations with rhythm in a way that meshes together perfectly.

Having had a few years elapse since hearing my last Masami Akita record, this seemed like a good time to step back in. The best thing about following this schedule with his work is that the variation and evolution he has shown in his overall sound keep things consistently fresh. Takahe Collage covers both his harsh noise past and his flirtations with rhythm in a way that meshes together perfectly.

The first two pieces clock in at around a half hour each, making this album not among the easiest to digest, but Akita excels within these longer frameworks.The title piece launches off immediately, presenting his more recent approach to electronic rhythms, but processed in his own idiosyncratic way.A paring of an blasting drum machine with lurching machinery underscores an erratic barrage of dive-bombing sine waves.

The rhythms continue throughout, evolving and shifting from synth pulses to insistent bulldozer surges to mix both distorted noise and pure, aggressive tones.At times the rhythms lock in and the remainder of the mix becomes more sparse, and a very Information Overload Unit era SPK sensibility bleeds through. Within the closing minutes, however, he goes for the usual balls out Merzbow noise roar.

"Tendenko" is more of a throwback to the mid '90s era of Merzbow (which is where my experience with him began), that goes for the walls of slowly shifting noise that the Incapacitants do so well, with a bit less of Akita's junk metal noise shining through.As old school as it is, there still is a buried, underlying rhythm that nods to his more recent works, covering both classic and modern sounds.

On the shorter (at a paltry 12 minutes) closer "Grand Owl Habitat," once again the rhythms are removed, with an overall dense, complex structure with individual pieces sliding in and out from one another:a rigid, stuttering rhythm with blasts of noise going off all around.It is similar to the title piece, but not quite as diverse, but due to its comparatively shorter duration it is not a problem.

After having burnt myself out on his release schedule in the latter part of the 1990s, my more contemporary experiences with Akita's output have been both more enjoyable and more rewarding.While my self-imposed distance from his always exponentially expanding discography may have improved my appreciation, Takahe Collage feels like more than that: a compelling work that is not just a great Merzbow record, but an exceptional noise album on its own.

samples:

Read More