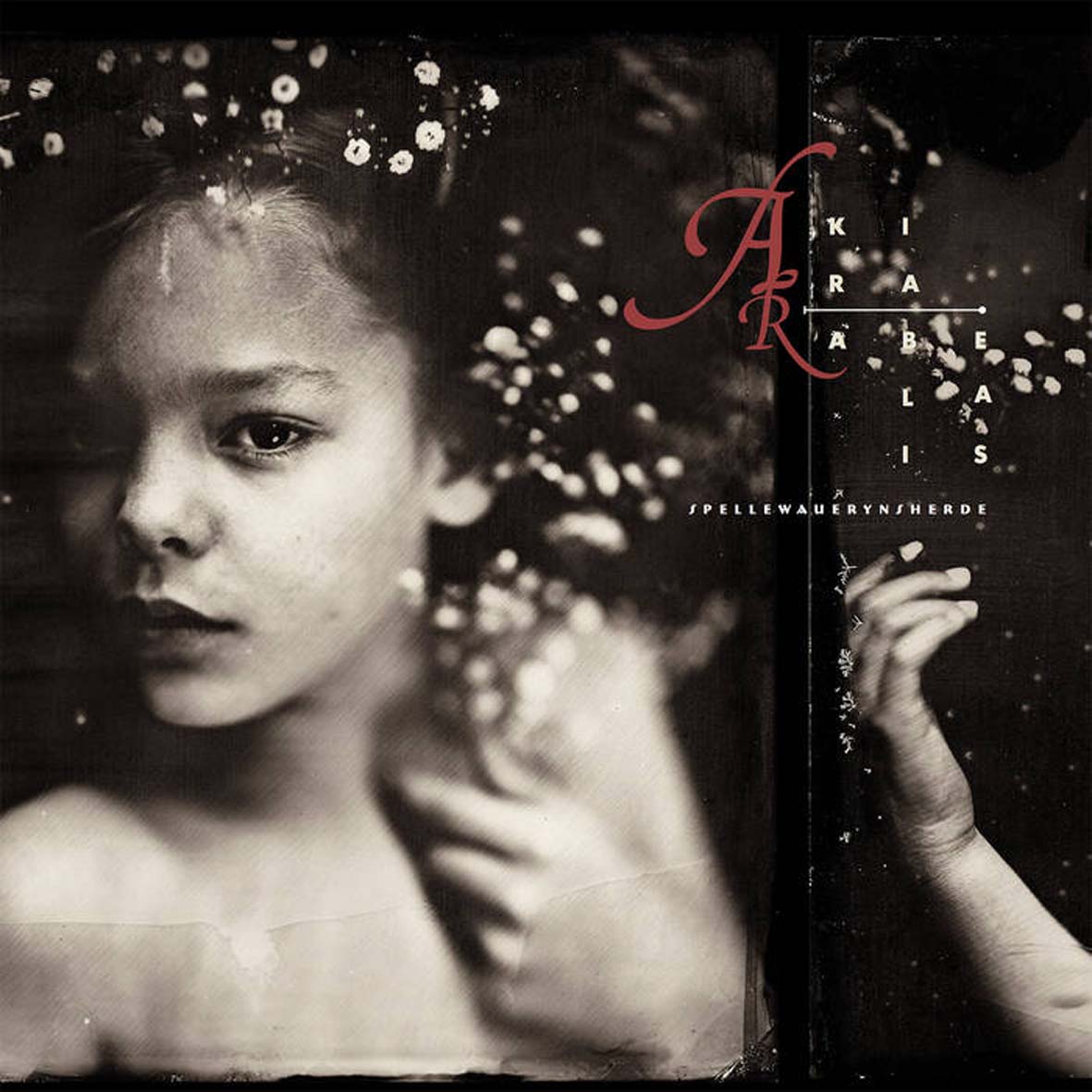

Akira Rabelais, "Spellewauerynsherde"

This singular album was originally released back in 2004 on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label, but Boomkat has just issued it on vinyl for the first time (along with quite a lot of accompanying praise about its status as an absolute masterpiece).  As curmudgeonly as I am, I have to agree–while the epic centerpiece of Spellewauerynsherde could probably benefit from somewhat sharper execution, these seven pieces cumulatively amount to quite a quietly staggering whole.  Rapturous beauty aside, Spellewauerynsherde is also quite a radical and inventive bit of sound art, as it was crafted entirely from feeding medieval choral music in Rabelais' self-designed Argeïphontes Lyre software, which seems to work by mutating, disintegrating, and recombining the source material.  Naturally, the sublime and unusual source material itself deserves a healthy amount of the credit for this album's timeless beauty, but Rabelais' transformative magic has unquestionably elevated it into something considerably more otherworldly and mysterious.

This singular album was originally released back in 2004 on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label, but Boomkat has just issued it on vinyl for the first time (along with quite a lot of accompanying praise about its status as an absolute masterpiece).  As curmudgeonly as I am, I have to agree–while the epic centerpiece of Spellewauerynsherde could probably benefit from somewhat sharper execution, these seven pieces cumulatively amount to quite a quietly staggering whole.  Rapturous beauty aside, Spellewauerynsherde is also quite a radical and inventive bit of sound art, as it was crafted entirely from feeding medieval choral music in Rabelais' self-designed Argeïphontes Lyre software, which seems to work by mutating, disintegrating, and recombining the source material.  Naturally, the sublime and unusual source material itself deserves a healthy amount of the credit for this album's timeless beauty, but Rabelais' transformative magic has unquestionably elevated it into something considerably more otherworldly and mysterious.

For some reason, I always thought Akira Rabelais was European, but it turns out at that he is actually a Texan currently based in California with quite an intriguing talent for cultivating enigmas and cryptic puzzles (his multi-lingual website is an especially impressive riddle).  Understanding that facet of his persona is often quite crucial for getting to the true depth of his work, particularly in the case of this album and its unwieldy Middle English-style song titles. For one, they seem to have no direct relation to the titles of the cannibalized choral pieces that provide the grist for Spellewauerynsherde, which were apparently forgotten recordings of an a capella Icelandic folk music ensemble made in the '60s and early '70s (found in a closet in Valencia, CA, naturally).  More intriguingly, they mostly reference significant (and sometimes bitterly ironic) events that shaped humankind's perception of God and heaven, such as the excommunication of John Wycliffe (who first translated the New Testament to English) or the English publication date of The Lives of Saints.  Other titles reference our increasing understanding of the vastness of the universe or early masterpieces of English poetry (Rabelais, being a true polymath, is also a poet himself).  It is not so much the idea of God that fascinates Rabelais, however, so much as it is the struggle to express the ineffable.  Naturally, trying to convey such elusive beauty and mystery through a composition is exactly the sort of impossible task that can consume (and destroy) a life, so Rabelais has wisely taken himself out of the equation as much as possible.  Spellewauerynsherde is like a once-majestic ancient church that has become a beautiful ruin from the tireless artistry of erosion and untended greenery, as Rabelais' software eviscerates the human component to extract its ghostly residue.

The degree of that transformation varies quite a bit from song to song, however, which is part of what makes Spellewauerynsherde such a fascinating album.  On the opening homage to John Wycliffe, the gorgeous female vocals sound fairly straightforward, but they texturally resemble a distant radio transmission heard over a quiet spectral drone.  Another bit of subtle magic is that the unsuspecting vocalist starts overlapping herself at various points, resulting in a strange and unpredictable duet of sorts.  The following John Gower-themed piece is similarly dreamlike and angelic, but sounds less like a radio transmission and more like two small choirs performing at opposite ends of a vast and reverberant cathedral. I would probably be perfectly fine with an entire album that continued in the rough vein of those first two pieces, but Rabelais starts to descend into stranger and more abstract territory with the next pair of pieces.  The first, "1440," is definitely the more bizarre of the two, dramatically slowing down the vocals into an eerie and corroded-sounding lament that sounds like it is bleeding into our world from the spirit one.  It sounds far more like an ominous, creeping fog than an Icelandic folk singer, which is quite a bit of transformational dark magic.  The album’s Lives of the Saints-themed centerpiece ("1483"), however, goes in quite a different direction, unfolding as a 21-minute epic of hazy and floating drone drift concealing fleeting snatches of lovely melodies that struggle to peek through the swirling mists.  I have conflicting feelings about it, as I would not have minded if its lushly amorphous and undulating heaven expanded to consume the entire album, yet it also seems like a long and unexpected lull in the album’s momentum due to its contextual relation to the more structured, melodic fare around it.  It feels like a great album unexpectedly dissolved into a different one.

I suspect that extended interlude was a thoughtful and deliberate choice though, as Rabelais saved some of his finest work for the end of the album and clearing some space to ensure that it made a maximum impact makes a lot of sequencing sense (though 21 minutes was still probably a bit excessive).  In any case, "Gorgeous Curves" is a feast of swooping, soulful and intertwining Siren-esque vocals that seem to dance and weave through an undulating mist.  There is even more going on than just that though, as the vocals also seem to drift in and out of focus and sometimes seem to lock into a stuttering loop for certain words.  It is quite a dynamic tour de force all around.  The closing homage to John Milton ("1671") is also a stunner, but one which removes almost all conspicuous evidence of artifice to leave just a naked and perfect vocal melody over an understated and vaporous bed of heavenly drones and what sounds like wind blowing across a lonely, remote microphone.  Not far into the piece, the singing dissipates altogether to leave only the gentle breathe of the wind and the elusive, whispy drift of the sublime underlying drones.  That lingering fade into silence is the perfect come-down after Spellewauerynsherde's glimpse into the divine and the purest distillation of Rabelais' iconoclastic brilliance on the album: the other six songs are certainly an integral and entrancing part of the journey, but the culmination is the almost complete negation of the artist and his ego.  With Spellewauerynsherde, Akira Rabelais is less of a composer than he is a humble and thoughtful facilitator, taking something already timeless, sincere, and beautiful and devising an organic and ingenious means of purging it of its last few earthbound touches.

- 1382 Wyclif Gen. II. 7 And Spiride In To The Face Of Hym An Entre Of Breth Of Lijf.

- 1483 Caxton Golden Leg. 208 B/2 He Put Not Away The Wodenes Of His Flessh With A Sherde Or Shelle.

- (Gorgeous Curves Lovely Fragments Labyrinthed On Occasions Entwined Charms, A Few Stories At Any Longer Sworn To Gathered From A Guileless Angel And The Hilt Edges Of Old Hearts, If They Do In The Guilt Of Deep Despondency.)