Alvin Lucier, "Criss Cross/Hanover"

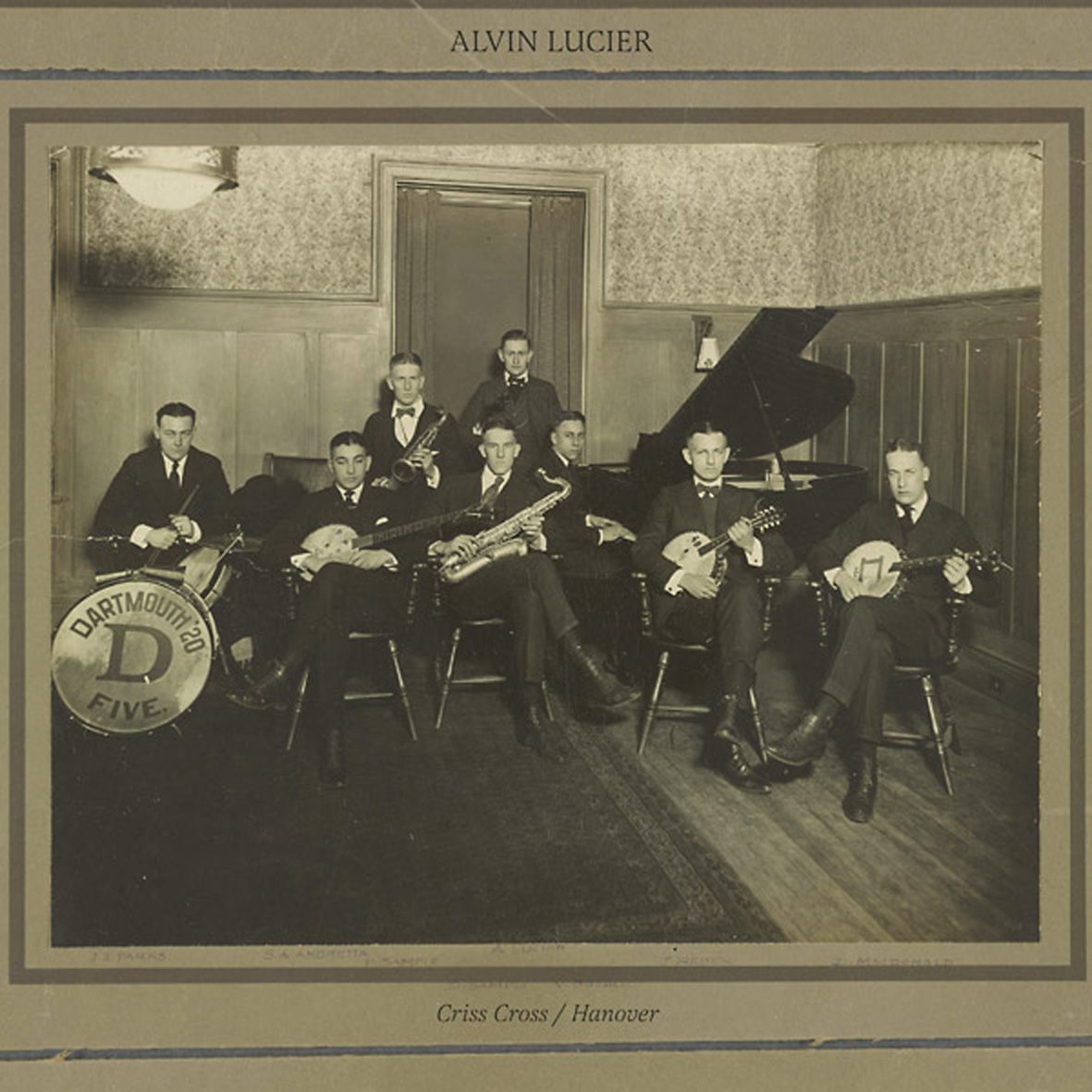

Now in his late 80s, Alvin Lucier has had a long career of radical compositions that explore phase interference, the resonance of spaces, and deeply unconventional sound sources. Although his output has certainly slowed in recent years, he remains as idiosyncratic and experimental as ever, recently becoming interested in unexplored possibilities for the electric guitar. The first half of this album is just such a piece, as "Criss Cross" was composed in 2013 for Stephen O'Malley and Oren Ambarchi (who perform it here). O'Malley and Ambarchi return for "Hanover" as well, albeit as part of an ensemble that roughly mirrors the 1918 Dartmouth Jazz Band pictured on the album cover (Lucier's father was the violinist). Needless to say, nothing on this album sounds even remotely like guitar music, though "Criss Cross" is not a dramatic departure from some of Lucier's previous work with competing phases. The nightmarishly spectral chamber music of "Hanover," on the other hand, is quite a large (and harrowing) surprise.

Now in his late 80s, Alvin Lucier has had a long career of radical compositions that explore phase interference, the resonance of spaces, and deeply unconventional sound sources. Although his output has certainly slowed in recent years, he remains as idiosyncratic and experimental as ever, recently becoming interested in unexplored possibilities for the electric guitar. The first half of this album is just such a piece, as "Criss Cross" was composed in 2013 for Stephen O'Malley and Oren Ambarchi (who perform it here). O'Malley and Ambarchi return for "Hanover" as well, albeit as part of an ensemble that roughly mirrors the 1918 Dartmouth Jazz Band pictured on the album cover (Lucier's father was the violinist). Needless to say, nothing on this album sounds even remotely like guitar music, though "Criss Cross" is not a dramatic departure from some of Lucier's previous work with competing phases. The nightmarishly spectral chamber music of "Hanover," on the other hand, is quite a large (and harrowing) surprise.

The prosaically titled "Criss Cross" is the first piece that Lucier ever composed for guitar and it has a very simple and aggressively minimalist premise: wielding E-bows, O'Malley and Ambarchi start at opposite ends of a semitone, then each of them slowly slides to the other end (and then back again…and again…and again).Thankfully, the chosen range falls in the lower frequency range, so the uncomfortably close harmonies that arise do not sound shrill at all.Instead, their proximity merely creates an oscillating pulse that speeds up or slows down depending on how close the two guitarists are to the same pitch.That steady, slow-motion see-sawing continues for roughly 16-minutes and it is the entirety of the piece.As such, its appeal is primarily conceptual, as it basically sounds like a droning thrum created by a wave generator of some kind, albeit with the length of the waves constantly shifting incrementally.Stylistically, it closely resembles some of Eliane Radigue's more purist drone work, though Lucier is perhaps even more austere.As such, the process itself is largely the appeal, as I never would have suspected that any guitars were involved at all if I did not know anything about the piece's background or its participants.

Though it is a considerably more "difficult" listening experience than the comparatively placid "Criss Cross," "Hanover" strikes a far more powerful and absorbing balance of concept and composition.Knowing its inspiration, it is also kind of a blackly funny piece, as few things could possibly swing less or clear a dance floor faster than Lucier's hazy miasma of queasy glissandi and uncomfortable, sickly harmonies.Ambarchi and O'Malley are additionally joined by a third guitarist (Gary Schmalzl), as Lucier replaced the banjos in the picture with guitars, but I am not sure it makes all that much difference who is involved, as any character or real distinction between the various musicians is essentially blurred into oblivion.Occasionally a single clear piano note will ring out, but the violin, saxophones. and guitars all smear and swirl together in a quivering haze.The best description of the piece that I can muster is that it feels like the hapless 1918 Dartmouth Jazz Band checked their tuning before launching into their set...only to have time immediately stop.Instead of their various notes ending naturally, however, all of the various pitches instead began to nightmarishly slide around in a kind of grotesque, slow-motion dance while they all watched in frozen horror.Naturally, I am exactly the target audience for something like that: "Hanover" is a wonderfully ugly and sinister fog of glacially evolving dissonance and tension.

I was not at all sure what to expect from this album, as I was a bit apprehensive about the idea of Lucier composing for guitars, particularly since O'Malley’s involvement suggested that some kind of awkward doom metal/conceptual sound art mash-up might result (both artists have strong and divergent signature aesthetics).Also, while Lucier never stopped working, it has been quite a while since he unleashed a provocative new major opus, so I had no idea where he currently was aesthetically.As it turns out, all of my concerns were happily unfounded, as Lucier has clearly not mellowed at all, nor did he allow Ambarchi and O'Malley's own aesthetics to hold much sway over his vision.This is pure, undiluted Lucier.In fact, this release not only befits his well-earned reputation as a restlessly inventive iconoclast, it actually bolsters it further.If this pair of new works has any flaw at all, it is merely that "Criss Cross" is essentially an interesting new way to revisit old territory rather than a complete leap into the unknown."Hanover," on the other hand, is a legitimate bombshell, viscerally illustrating that Lucier still has an impishly heretical approach to modern composition and that it has some very sharp teeth.