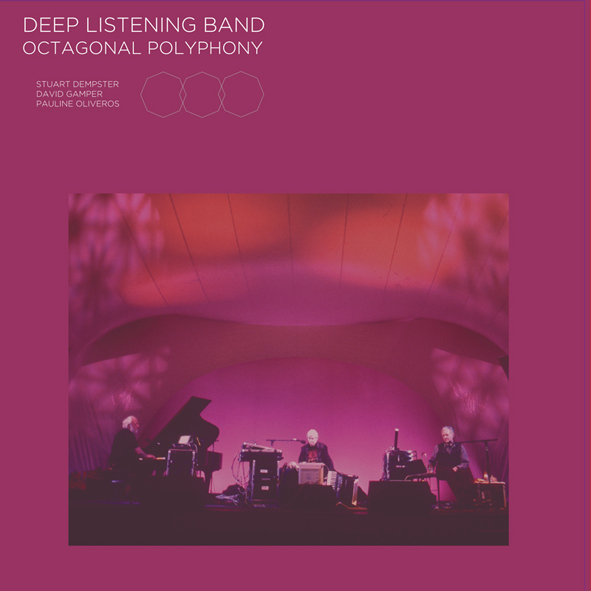

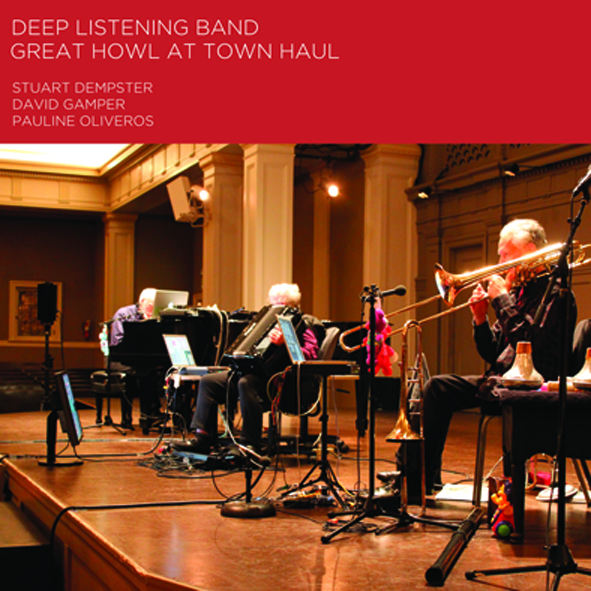

Deep Listening Band, "Great Howl at Town Hall" and "Octagonal Polyphony"

Pauline Oliveros' best-known and influential work is 1989's Deep Listening, recorded in a massive, reverberant cistern.  In the years since that landmark effort, Pauline has founded The Deep Listening Institute, the Deep Listening Band, and performed many mesmerizing concerts in her unending crusade to explore the untapped potential of space, place, and (of course) reverberation.  These two previously unreleased albums capture some of the final recordings her band made with (the late) long-term collaborator/pianist/electronics wizard David Gamper. Although both performances occurred over the course of a January 2011 Seattle residency, they almost sound like two completely different bands: Octagonal Polyphony luxuriates in sublime, slow-motion drones while Great Howl becomes pretty nerve-jangling.

Pauline Oliveros' best-known and influential work is 1989's Deep Listening, recorded in a massive, reverberant cistern.  In the years since that landmark effort, Pauline has founded The Deep Listening Institute, the Deep Listening Band, and performed many mesmerizing concerts in her unending crusade to explore the untapped potential of space, place, and (of course) reverberation.  These two previously unreleased albums capture some of the final recordings her band made with (the late) long-term collaborator/pianist/electronics wizard David Gamper. Although both performances occurred over the course of a January 2011 Seattle residency, they almost sound like two completely different bands: Octagonal Polyphony luxuriates in sublime, slow-motion drones while Great Howl becomes pretty nerve-jangling.

Releasing actual albums has always been something of a tricky and flawed situation for the Deep Listening Band, as the way that sound is experienced is a very large part of their art and that can be quite site-specific.  Some aspects of their vision translate well, such as the 45-second reverb of Deep Listening's cistern or the way that overlapping layers blur together and interact.  However, approximating the omnidirectional immersion of an actual concert seems pretty damn impossible due to the unusual number and location of the speakers involved.  And then, of course, there is the added impact of the band's self-designed Expanded Instrument System (EIS), which I do not understand at all, but seems to mess with both time and space and allow players to "perform in the past, present, and future simultaneously."  The gist is that it sounds like the band is a hell of a lot larger than it actually is (a trio).  Trombonist Stuart Dempster actually states in the liner notes that countless hours of listening, re-listening, mixing, and remixing managed to capture a hint of the experience and that seems like a plausible estimate to me.  This music doesn't strike me from all directions at once, but it undeniably has a unique presence and power.  It doesn't hurt that the music itself is pretty amazing too.

"Bell Dance," the first of two pieces on Octagonal Polyphony, is appropriately based upon a rippling lattice of twinkling, chiming bells.  It is not especially dance-able though, as it is filled out by lengthy sustained tones from woodwinds and Dempster's trombone.  Gradually, however, it becomes more and more disorienting, as occasional dissonances start to creep in and something that sounds like a plucked violin begins playing an insistent motif that makes it all sound like a badly derailed Steve Reich piece.  While it undeniably achieves an appealing degree of complexity and unpredictability, it gets a bit too bombastic and trombone-heavy for my liking at about the halfway point.  It regains some momentum briefly though, as a snarled surge of didgeridoo heralds quite a cacophonous interlude.  The last five minutes or so end up being pretty weird, jumbled, and dissonant, leaving me a bit conflicted about the piece.  I think the actual content is ultimately a bit lacking, but it is so dense, multilayered, and dynamic that it almost overcomes that...almost.  I definitely give them credit for making didgeridoos sound scary and heavy though.

"Dreamport" is built upon a low, undulating throb and some shimmering, uncomfortably dense accordion harmonies.  Given the involvement of the EIS, it is pretty impossible to figure out who is playing what and when, but the piece quickly becomes incredibly dense and vibrant with overlapping textures and overtones.  Though I can pick out Dempster's trombone and some very ominous didgeridoos, it achieves such a quavering, skittering immensity within minutes that individual instruments become irrelevant.  More importantly, it is an absolutely wonderful piece of music–I could not be happier that it unfolds for 22-minutes and found myself gradually turning it up louder and louder.  While "Dreamport" ostensibly adheres to the structure of drone music, it is so massive, dynamic, and uneasy that it bears almost no resemblance to most other work in the genre.  To a certain degree, it captures the Deep Listening Band at their sustained best, but even that pales a bit when compared to the more disturbed and visceral companion effort discussed below.

Great Howl at Town Hall deceptively begins in very similar droning fashion to Octagonal Polyphony, as "Town Haul" opens with throbbing drones, growling didgeridoo, and deep, accordion-produced breath-like noises.  However, the periphery is a bit more jagged and unhinged: amidst the massing sustained tones, there are all kinds of sharp whines and squeaks, as well as various unidentifiable strangled squawks. By the halfway point, it ceases sounding like drone at all and more closely resembles an especially hallucinatory horror film soundtrack...and then it continues to intensify.  By the end, I started to seriously wonder if I was about to be attacked by a flock or swarm of something ill-intentioned.  That dissonant, uneasy atmosphere pretty much sticks around for entire album, though the tension admittedly ebbs and flows quite a bit (it would be overwhelmingly uncomfortable otherwise).

"Great Haul" is initially a bit less disquieting, as it merely sounds deranged rather than menacing: it has an odd, lurching rhythm and the blurting music sounds drunk, chromatic, and sometimes eerily speech-like (presumably some kind of neat trombone/wah-wah pedal trick).  It is nevertheless an incredibly complicated piece and various layers of field recordings and dissonant string-like noises rapidly escalate into a crescendo that is about as apocalyptic and overwhelming as it gets.  It must have been very memorable and surreal for concert attendees to experience such face-melting intensity from a trio of senior citizens armed with accordions and trombones.  Though it eventually subsides into a shimmering coda with lingering flashes of dissonance, it is essentially 12-and-a-half minutes of unbridled awesomeness that is scarier and more innovative than 95% of the extreme music being made today.

The longer "Great Horned Howl" starts off on an unexpectedly pastoral note, as Gamper's piano ripples amiably without any significant threat of being overwhelmed by dissonance.  Notably, he manages to simultaneously call to mind both Steve Reich and Conlon Nancarrow, which is an unusual feat indeed (his Reich-ian repeating patterns start to multiply and some are sped-up and pitch-shifted to an inhuman degree).  Around the midpoint, things settle into a strange gibbering and skittering lull before getting very weird indeed.  I wish I could I say knew what was going on, but I definitely do not–all I know as that the piece begins being populated with cartoon voices and Halloween sound effects like howling wolves and cackling witches and that it is all bat-shit crazy.  I think there may also be some monkeys and birds thrown into the mix as well.  While I appreciate being totally blind-sided and wrong-footed by a piece of music, it is simply too unhinged and outré even for me (especially at nearly 20-minutes long).

The album closes with "Growl Howl" (someone in the band is clearly fond of absurdist wordplay), which revisits the skittering/gibbering chromatic aesthetic of the previous piece, sans sound effects.  Then it unexpectedly snowballs into a brief crescendo even more intense than that of "Great Haul," complete with jarring aftershocks.  It is probably one of the heaviest things that I have ever heard, given its context and suddenness.  Curiously, things become subdued, mournful, and strangely beautiful after the outburst, though an ominous rumbling quickly threatens to envelope my welcome respite of conventional beauty.  The rumbles eventually triumph, but the doomed, melancholy motif somehow becomes even more moving as it is being consumed.  The last five minutes of the piece don't quite ever recapture either the visceral impact or the emotional resonance of the preceding ten, but Oliveros' uneasily dissonant accordion settles into a steady rhythm that calls to mind slow, deep breaths, ending the album in a completely appropriate way (like recovering from a traumatic scare or other harrowing experience).

Normal rules for music criticism don't quite feel like they apply to these albums, as they seem somehow more vivid and multi-dimensional than other music: the content is almost secondary to the immensity and vibrancy of the sounds being created.  While neither album is an unqualified success and the trio make a number of musical decisions that I am not entirely fond of, I am nevertheless left feeling like that does not matter terribly much at all.  In fact, I feel like I indirectly experienced something rather monumental–when Dempster, Oliveros, and Gamper (along with unsung hero/engineer Michael McCrea) are at their best, they are absolutely staggering and seem more like a force of nature than a band.  The Deep Listening Band was (is?) a wholly unique phenomenon: while it is hardly a secret that bizarre and dissonant avant-garde music is infinitely more palatable when coupled with presence, immediacy, and gut-level power, no one else has perfected that difficult balance quite as beautifully as this.

Samples: