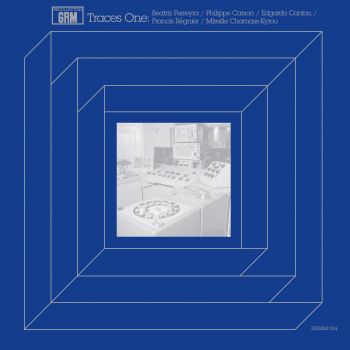

These two compilations highlight some of the lesser-known composers who have worked at the Groupe de Recherches Musicale (GRM) in Paris. The first volume charts some of the obscurities of the 1960s while the second volume concentrates on works from the 1970s. Taken together, the Traces collections are a fascinating parallel to the reissues of major GRM albums that Recollection GRM have been doing, showing that equally maverick work was been done by names less familiar than Pierre Schaeffer or Luc Ferrari.

These two compilations highlight some of the lesser-known composers who have worked at the Groupe de Recherches Musicale (GRM) in Paris. The first volume charts some of the obscurities of the 1960s while the second volume concentrates on works from the 1970s. Taken together, the Traces collections are a fascinating parallel to the reissues of major GRM albums that Recollection GRM have been doing, showing that equally maverick work was been done by names less familiar than Pierre Schaeffer or Luc Ferrari.

Traces One begins in fine style with Beatriz Ferreyra’s "L’Orvietan," a deeply atmospheric piece from 1970 that moves between two approaches during its course. The first half is given over entirely to electronic music which sounds unnervingly like the noises that open "The Avatars" from Coil’s 1999 masterpiece Astral Disaster. However, Ferreyra pushes the listener further and further from their comfort zones as her music gets more intense as it progresses. The switch from electronic to concrète makes things stranger still, the vaguely humanoid sounds becoming a presence in the room which cannot be ignored.

Ferreyra’s oddly organic work is contrasted by Philippe Carson’s 1961 piece "Turmac" which takes the sounds of a cigarette manufacturing plant as its base. The mechanical, rhythmic work attempts to take the obviously machine-derived recordings and subject them to various stages of manipulation in order to detach the music from its source. It is still as alien sounding as Ferreyra’s piece but in a completely different way. Here, the idea of musique concrète is given full focus as Carson utterly breaks down the boundaries between factory noise and music.

Atmosphere continues to be an important concept on side B as Francis Régnier’s "Chemins d’avant la Mort" can testify to. A meditation on dying, it builds from almost silence with Régnier increasing the intensity to a level that would satisfy Merzbow before dropping off to a death-like silence, with only the barest, tinnitus-like ringing left. It is the shortest piece here but undeniably the one with the most impact. It leads quite perfectly into Mireille Chamass-Kyrou’s "Étude I" from 1960. This comes across as more of a technical exercise compared to the other pieces on Traces One but it is interesting beyond the techniques. Again, the power of the music stretches beyond the sounds heard and into the feelings generated in the room it is being played; Chamass-Kyrou acting as a psychologically minded composer rather than a musically minded one. It is a pity that no other pieces by her seem to exist (this piece was included on an INA GRM box set about ten years ago and that’s it) as "Étude I" is so tantalising in its possibilities.

Traces Two shifts the time frame forward by ten years and the difference is immediately noticeable in Dominique Guiot’s "L’Oiseau de Paradis" from 1974 which is as colourful as its title suggests. Guiot attempts to musically reproduce the fast edits and sudden scene changes of film with great success, the dramatic turns that run through the piece make it almost impossible to break my attention away to do anything else (such as writing this review!). Aside from its form, it is obvious that a new era had begun in the GRM as the instrumentation sounds so much more modern and controlled here compared to the pieces on Traces One and Guiot uses these tools to his advantage, creating exciting textures that truly do sound like the future even today.

Traces Two shifts the time frame forward by ten years and the difference is immediately noticeable in Dominique Guiot’s "L’Oiseau de Paradis" from 1974 which is as colourful as its title suggests. Guiot attempts to musically reproduce the fast edits and sudden scene changes of film with great success, the dramatic turns that run through the piece make it almost impossible to break my attention away to do anything else (such as writing this review!). Aside from its form, it is obvious that a new era had begun in the GRM as the instrumentation sounds so much more modern and controlled here compared to the pieces on Traces One and Guiot uses these tools to his advantage, creating exciting textures that truly do sound like the future even today.

While taking a more traditional musique concrète approach, Pierre Boeswillwald’s "Nuisances" from 1971 also takes a less than traditional approach to composition by focussing on the mistakes and the sounds that are the opposite of what he would select if he was to do this based on what sounded best. On paper, it sounds like he invented glitch music in the early '70s but "Nuisances" sounds very different to what we would consider glitch or even noise now. It actually sounds rather great and to my ears, is totally in keeping with what Bernard Parmegiani has been doing with the GRM over the course of his career. Out of the four pieces included on Traces Two, it stands out as being the most conservative (though obviously that term is used very loosely even in this context!).

Rodolfo Caesar’s "Les Deux Saisons" could have been made in the last ten years. A seemingly simple layering of tones, it is actually a complex work of recording and manipulating idiosyncratic instruments over a course of two years. Combining sounds generated from the Baschet brothers’ cristal baschet (an "organ" composed of rotating glass rods tuned chromatically and played with moistened fingers that was popular amongst composers in the GRM) and a frequency modulator, Caesar achieves a most unusual and haunting sound that sits somewhere between pure electronic music and natural acoustics.

Traces Two concludes with "Pentes by Denis Smalley. Recorded at around the time Smalley was finishing up one of the very first diplomas in electroacoustic music, the piece sounds sophisticated in its use of complex manipulations of recorded sound along with relatively untreated bagpipes to create a harmonically rich environment which feels at home both in the future and the past. The appearance of the pipes towards the end is like a phantom slowly appearing from within a deep fog, leading the listener home.

While I am impressed with the Recollections GRM label in general, these two compilations are clear winners in my mind in their scope and the fact that this is mostly unknown music to most listeners aside from seasoned electroacoustic collectors. Even then, some of these pieces are previously unissued or buried in dense compilation sets and given little or no space to be explored. Presented here in these relatively uncluttered albums, it is possible to get a deeper understanding of the range of work being undertaken at the GRM and being able to hear beyond the more famous works by its brightest stars.

Read More